In which I explore my beloved friend’s family tree and confirm a painful truth

“When my mamma and daddy started their family,” Mary began. “They didn’t have anything, so they had to work the farm.”

Mary, my childhood caregiver, and I were sitting together in her daughter’s home just south of Atlanta studying the notes Mary had spent days preparing. By “the farm” she meant a cotton farm owned by a white family who by the time Mary’s parents married employed her paternal grandmother as a laundress and her great-grandmother as a cook.

“Were they sharecroppers?” I asked. I was presuming, I suppose, but with good reason. It was 1935. Mary’s parents lived in Hurtsboro, a tiny town in a county pushed up against the Georgia border in Alabama’s “Black Belt,” so named for both its rich soil and its historic dependence on the labor of African Americans, originally as enslaved workers and later, as tenant farmers. These tenants, who during the Great Depression accounted for well over half of all farmers in Alabama, “shared” profits earned from the cotton and other crops they harvested for the farm’s owner.

Or that was the theory.

“Humph …” Mary said with a smirk. “Sharecropper? I don’t know about that. They didn’t share nothing.”

With this she let go a sharp laugh. I smiled, marveling at her sassy wit and how it had survived the years. She was spot on, too. The bits landowners shared were most often so meager that tenant farmers struggled to break even after each year’s harvest. Sharecroppers who tried to save enough to move on to some other life would labor years, decades even, before they felt secure enough to leave. Even then they rarely had the means to purchase land of their own.

“My grandmother Ellen Walker had married a Cochran,” Mary went on. “But it didn’t work out, so my daddy was the man of the house. He had to work in the fields even when he was just a boy, to help support the women.”

Mary’s women, strong women who would end up raising her, were her grandmother Ellen, Ellen’s mother Caroline—“but everybody called her Ca-line,” Mary added with a broad smile—and Caroline’s mother, also named Ellen Walker. I asked, but Mary wasn’t sure exactly where or when the first Ellen or Caroline were born. Hmmm. Perking up, I slid to the literal edge of the couch we shared. I tinker a bit with genealogy (ok, it’s my favorite rabbit hole), and with tingling fingers I asked Mary’s permission to do a little research into the Walkers.

“Why sure,” she said after a pause. There was a touch of something in her soft features, unease, maybe even worry, but I brushed it off.

Parsing out birth places and hidden relationships and surprising connections is a lot like solving a puzzle. Though following a hunch through the generations can take weeks, I love the warm and fuzzy feeling that a successful search brings. I fired up my Ancestry account later that day, and dug in. The 1930 census suggested that the older Ellen Walker, Mary’s great-great-grandmother, was 106 years old that year. 106!!! Alas, this detail is likely exaggerated … Ellen was alive when Mary was a young child in the late 1930s. Her actual birth year is reported in a different census as 1840, in another as 1835, and on and on. But no doubt, Ellen Walker the elder was at least in her nineties in 1930 and was born, in rural Alabama, decades before the Emancipation Proclamation. Ellen first shows up in public records, along with three daughters and a son, in the Census of 1880 as a farm laborer in a community called Glennville. A ghost town now, Glennville sat about twenty miles south of Hurtsboro at the northern tip of what was then Alabama’s most prosperous cotton producing region.

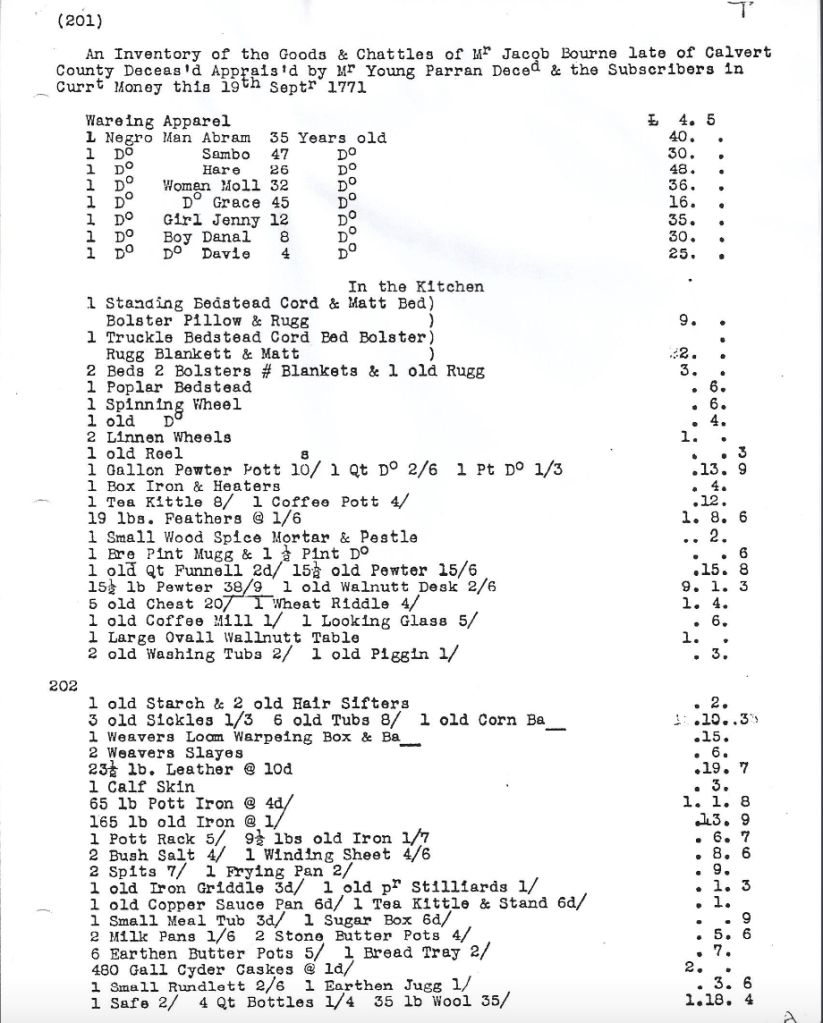

In spite of Ellen Walker the elder having been born in 1840 or before, she is not listed in the censuses of 1840, 1850, or 1860. Although free people of color are listed in these censuses, enslaved men and women show up as anonymous tick marks in separate “slave censuses” reported by landowners and identified only by race, age and gender. Odds are high, then, that in the antebellum years, Ellen’s existence was noted by one of these tick marks and that she worked as an enslaved laborer in the cotton fields of a Glenville plantation. At the end of the Civil War, she likely stuck around Glenville, as many of the formerly enslaved did, to work the same or another farm nearby with her young family, which included her second child, Mary’s Ca-line, listed in that 1880 Census as ten years old.

I kept burrowing, hoping to find a reference to the elder Ellen’s husband, or her parents or siblings, but came up empty. No census listings, no birth or death certificates, no marriage license. Feeling anything but warm and fuzzy, I paused my search. A deep loneliness filled me to think of Mary’s second great-grandmother, a woman who lived such a long, brave, rich life, perched alone atop the Walker branch of Mary’s family tree as if she’d self-birthed when in reality she had ancestors dating back hundreds of years, ancestors who had survived the cruelties of slavery, the unfamiliar environment and diseases of a new world, the brutality of the Middle Passage, but died unnamed and unheralded.

I thought of Mary’s hesitance about my search and sensed she wouldn’t be surprised to hear that members of her family were brought to this country against their will, forced into backbreaking labor, among other things, and treated as less than human. When we next met, we chatted a little about her great-great-grandmother. She confirmed the names of Ellen’s other children that show up in that 1880 Census. I probed her a bit to see if she might remember any other Walker ancestors. She didn’t and I left it at that. She knew where Ellen’s branch led and to dwell on it could only bring pain. A little at loose ends, I opened my phone and zoomed in on a few other things my search had turned up—a photo of her mother’s mother, Bettie Lou Tyner James. Born in 1879, she lived to 91. ”Why that’s Ma Bettie!” Mary exclaimed. Then a pic of her Cochran great-grandparents, Elias and Georgia, on their wedding day, and copies of several marriage certificates, her parents’ and grandparents’ and even one for Elias and Georgia, married in September of 1890.

Holding the phone close to her face, Mary thanked me, her voice filled anew with her characteristic joy. I told her it was nothing. I liked genealogy and hoped to discover more. We both felt better for having looked over these images together, a little less lonely to think of Ellen Walker and her lost parents and grandparents, and of Mary’s many other unnamed ancestors, those whose blood she shared and whose strength and courage live on in her children and grandchildren.