“We had a sack we carried over our shoulder,” Mary said. “You picked off the hard brown bolls, they were like a little hard flower with a thick husk and the end of it was sharp and sticky. You had to take off the boll and pull out the little seeds before you dropped the cotton in your sack.”

I Am Mae Mobley

My birthday is in July. Mid-summer, any way you slice it, prone to the lingering 4th hangover and hot and gluey the hemisphere around. In Atlanta, my home town, July 8th often dawns drowsy and nondescript, a day when traffic is strangely light and folks wind up sipping icy beverages by the pool or streaming baseball in front of an AC vent. I mean, think about it … has anything of true significance ever happened on July 8th? I looked it up, and–not much. In 1835, the Liberty Bell cracked, though reports vary. It might have been the 12th. In 1907, whoop-dee-doo, Ziegfield opened his first follies in New York City. 1918: Hemingway was wounded on the Austro-Italian front but macho-man that he was, survived to pen his oeuvre. 1947: a UFO crashed down in New Mexico (or not), and in 1949, Wolfgang Puck was born, followed by Kevin Bacon in ’58. Hmmm.

To be honest, I used to feel a little sorry for myself for having my special day during this time of scatter, a summer limbo void of classroom cupcakes and piñatas. When I was a wee thing, my birthday parties tended to be poorly attended at best, fleshed out with persons my mother rounded up to stand in for my wider circle of friends, who were off at camp or beach-combing with their families. Nowadays, I often vamoose on July 8th myself, and really, as the calendar turns, what could be better than to flit out of town and have one’s birthday forgotten altogether?

But in July of 2016, I was home in the city. My birth-week went haywire from the start. On Tuesday the 5th, Alton Sterling was shot by police in Baton Rouge, another possible case of color-coded fear having led to the panicked and deadly misuse of power. Ditto on the 6th, when a routine traffic stop in suburban St. Paul ended with Philando Castile, an African American man, dead. Yet sadly, if not for what happened next, on my birthday eve, these events might have become little more than tragic footnotes in the on-line version of “On This Day in History.”

As yet unaware, I woke on the 8th to the joy of family texts and emails sent at the crack of dawn and a birthday poster lovingly drawn by my youngest son. But before I could pour my first cup of Joe, I found myself longing for the dull birthday anonymity I used to lament. On the kitchen television, an endless loop of chaos and gunfire on the streets of Dallas during an otherwise peaceful protest, a dozen policemen sniper-shot, five dead.

Mass shooting number 150 or so on the year, and we were hardly halfway home. I don’t know how many of these were racially motivated, but I’d bet a silver dollar they were all rooted in hate, the kind of hate that when kindled by emotional instability is likely to fester in the heart of the dispossessed, the kind of hate that so often meets with an ironic end, where one desperate individual lashes out against others equally marginalized, but for different reasons, the kind of hate I believe is at its core self-hate, and in the end bound to turn on itself, but only after havoc has been wreaked. Consider the deeply troubled and alienated white drug addict who guns down African Americans in Charleston, in a place of worship historically vital to the Civil Rights movement; the pathologically angry Muslim American, isolated within the country of his birth, who opens fire on his gay neighbors; the mentally disturbed black war vet who ambushes white police officers as they monitor citizens of varied races seeking to prevent future incidents of policing gone sour.

I’m over-simplifying, and even so, my head was spinning. The line between villain and victim grows more muddied every day as hot-button issues like gun legislation, immigration, mental health care, police brutality become so multi-layered and complicated it’s impossible to discuss them without simplifying. But enough. I don’t write today to enter a particular dialogue. I write because as a white woman born and raised and still living in the American South, my bones ache with a helpless sorrow I can’t well reckon with. I write in the hope that putting words to paper will help me lasso emotions I can’t otherwise make sense of. And already I’ve erred. Sorrow isn’t the right word. What I feel is closer to despair. That we as Americans, no matter the shade of our skin, continue to wrestle with the violent manifestations of the same brand of hate, the same demons that have threatened our nation since its inception, is unthinkable.

On a long flight home that summer of 2016, I flipped through Delta’s offerings and came across The Help. I’d seen it before, and on both occasions found it more moving, more true-to-life than I expected (I boycotted the book, perhaps unfairly, having heard it was sappy and overdone). What I’d forgotten was the uncomfortable blend of warm recognition and biting shame the film dredged up in me. In some ways, I am Mae Mobley Leefolt, the little white girl loved and cared for by Aibileen Clark, the Black woman the Leefolts referred to as their maid. Mae Mobley was born, fictionally speaking, in August, 1960, in Jackson, Mississippi. I was born in July, 1960, in Atlanta. Mae Mobley had Aibileen. I had Mary Darian, the young woman who worked at our house not every day but often enough I thought of her as family. When in the final scene Mae Mobley calls out to Aibileen, “You’re my real mother!” (yep, pretty sappy), my heart leapt in spite of itself. Though my mother wasn’t negligent like Mae Mobley’s, Mary was sort of her co-mother, an energetic, funny, hands-on, more hip role model than Mom, forty-one when I came along, was capable of being.

And Mary was Black. And far too smart, too gifted, for her position. She had small children of her own someone else cared for while she raised us, no doubt earning less than she deserved. Yet she changed my diapers and sang me to sleep. She picked me up from school and brought my dog along to greet me. She fried a chicken for us on Friday afternoons. Later, she wrote me at camp when I was homesick, sharing details about what my brothers were up to (“Tommy and I cleaned out his closet. He hates making decisions”), complimenting my mother’s sewing projects or cracking a little joke, usually at her own expense. Sometimes she signed off, tongue-in-cheek, “The Maid.” My favorite letter (from Mom’s Attic, of course) is written on two sheets of construction paper torn crookedly across the top and quadri-folded to fit the envelope. After dating the letter, Mary wrote “cheap paper” in parentheses and a few lines later elaborated: “This paper is slightly uneven–like the writer.”

Mary left us when I began junior high, taking a job at the hospital where I was born. Mary made a career there, earned a few promotions and stayed on for twenty years. We kept in touch, a phone call now and then, quick visits during family weddings, funerals. Then, a long gap of time passed with little contact until the day of my mother’s funeral. As I walked out on my brother’s arm, I caught sight of Mary at the end of a pew. White-haired, a little stooped, she somehow wept and smiled at once. I stopped, and we hugged each other’s necks and cried together. She told me how much she’d loved my mother, her friend, how she misses me, and all the Mattinglys.

During the weeks after the violence of summer 2016, I thought a lot about Mary, then eighty, and felt that same warmth tempered by shame that movies like The Help can rustle up. I like to think our bond was unusual, deeper than most of its type. Mary was my friend and yet, history says what we and thousands of other Black-white, housekeeper-child duos of the fifties and sixties shared was tainted. History says that if not for the evils of slavery, these bonds wouldn’t exist, that perhaps they shouldn’t have existed. I can’t deny the truth in this, but then, what do we do with the warmth, the love, that remain?

It occurred to me that other than what I share here, I didn’t know Mary Darian’s story. I didn’t know how she, eighteen when my parents hired her, managed to break the cycle of domestic service. I knew nothing, as her white baby of the 1960s, about the sit-ins and marches, the tear-gas and beatings, that were happening across town, maybe in her neighborhood. I didn’t know who or what she might have lost to the long slog of the Civil Rights struggle. My parents, like Mary herself, were determined to shield me from these seminal, sometimes violent events that would shape our lives. In this, my ignorance of Mary’s story, lies a valid basis for guilt and shame. I can’t change history. I can’t make amends for actions taken by my forebears, though I regret and renounce them. I can’t go back and rearrange the circumstances of my relationship with Mary, but that summer I realized I could at least do what another one of Kathryn Stockett’s characters, Skeeter, does. I could learn Mary’s story. I owed her, and myself, that much.

Late that July, I dug up one of my mother’s old address books and skimmed a few pages in. There it was, between Coleman and Davis: Mary Darian. Unlike other entries, it was not written in my mother’s script. Mary had jotted in her name and address herself—of course she had—in the same big beautiful hand I’d thrilled to see in letters she wrote to homesick me at camp. Mary’s entry, unlike others, was neither scratched through nor updated. Maybe, I thought, she still lived in that tidy house I’d visited. Maybe she had the same landline my mother used to dial up whenever she missed the woman she thought of as much more than the help.

There was only one way to find out. I pushed the home button on my cell phone, and made the call.

If you’d like to read more about my journey with Mary, click here to access “Afternoons with Mary,” the sequel to this post. Many thanks for reading!

Shaking off the Dust

When I launched this site a decade ago (!), I expected to share a few posts about the exhausting, cathartic, sometimes funny and strangely exhilarating process of cleaning out my parents’ attic. One damp box of mid-20th century toothpicks led to another, and thanks to support and input from readers like you, I learned that sharing family stories not only kept my late parents alive, it sustained me through the joys and sorrows of the years that followed.

In that spirit, and because honestly, how much more can be said about faded photographs and mildewed button boxes, I’ve decided to creak shut the attic door and launch a new site. It’s called “Why the World Wags,” and in it, I plan to wax on about well, whatever grabs me as I move along through life. Ten years on (!!!) from that first post here in “My Mothers’ Attic,” I find myself teetering at the edge of what some call the golden years. Has there ever been a more obvious euphemism? Golden in the sense of being burnished by life perhaps, but there are days when the world around me seems cast in the gray light of dusk. And yet! At other times, that world seems to sparkle in a way I rarely noticed when I was younger–when a bluebird lights on a leafy branch in our back garden, his feathers aglow with morning light, or when I’m able to revisit a place I’ve come to love, like the brilliant waters off the coast of Belize pictured above, or when my toddler granddaughter reaches for me, smiling, and calls my name (which at her bidding, seems to be “Gaga”).

Golden moments, every one.

If you’d like to join me on my continued journey, here is the first newsletter/post from the new site. I’ll be migrating some of my more popular posts from here to there, usually with some editing, but I’ll leave the Attic open a good while, too. To visit the new site itself, just click below. If you like what you read, consider subscribing (s’il vous plaît!)!

https://marthamattinglypayne.substack.com/

Thanks for reading, always, and I hope to see you in Why the World Wags!

The Places We Become

Tuesday, January 28th, 2025, would have been my brother John’s 75th birthday. I woke thinking, Oh, I need to call John today. How strange, how wrong, it felt not to have one of our cross-country chats. Like me, John was born and raised in Atlanta. When he was around thirty and I was twenty-ish, he moved to San Francisco. There, he became a clever, in-demand, pen-wielding ad man, later a creative director who befriended the celebrities he hired for shoots or met in Marin County on his children’s ball fields and school auditoriums, celebs like Steven Spielberg and Téa Leoni. Over the years, those of us living our quieter lives back east kept hoping something would draw John home to stay. We missed our smart gentle brother, but California had lassoed his heart for good. Our southern charm and Georgia sunshine were no match for the fog rolling in off the mighty Pacific, the hills rising impossibly beneath the wheels of the cable cars, the giant conifers piercing the skies, the 49ers, and the quirky beach towns where John summered with his family.

John’s son and daughter grew to love San Francisco and Marin County with a passion to rival his. On Saturday, the first anniversary of his passing, Ben and Laura Lee held a memorial service in Stinson Beach, the quirky beach town John loved best. Tucked below Mount Tamalpais in West Marin, Stinson curves along a peninsula east of Bolinas. Seals swim and dive for their dinners in the lagoon on the peninsula’s north side. Egrets and herons glide over the sea and roost in the trees.

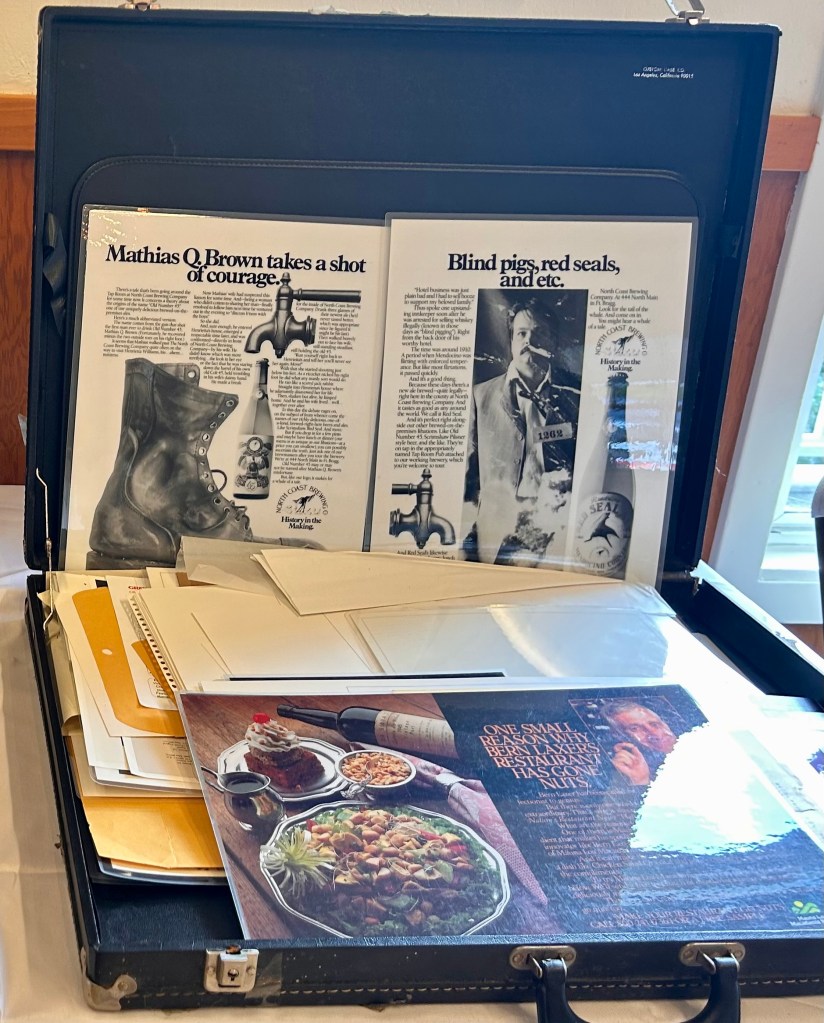

Our family had visited John often in recent decades, and these wonders of Stinson, the memorial itself, brought him back to life in bittersweet ways I hadn’t expected. Ben and Laura Lee set up a display that featured laminated copies of the print ads John created. His original portfolio briefcases spilled their treasures: John’s brainstorming notes, folders holding rough drafts, more ads, including one for a brewery that features John himself striking a gangster-like pose. A longtime colleague told tales of John’s ad days and reminded us he earned a professional nickname–Mad Dog Mattingly–when he once shed his Southern gentleman skin to stand down a difficult and demanding director. John’s children shared stories about John as a California Dad–the hours he spent shoveling snow at their cabin in Lake Tahoe to create luge-worthy troughs for their sleds, the steak dinners and fish fries he prepped, his habit of pulling over at every turnout during countryside drives–“Take it in, kids” his favorite refrain as they gazed together at the sea, the mountains, the dramatic cityscape of San Francisco. As her comments drew to a close, Laura Lee spoke of John’s close relationship with his grandson, her five-year-old son Ollie, who called him Poppy. With that, Ollie rose from his seat and lifted a basket from a table near the front. “California poppies,” Laura Lee said as Ollie handed out small bags of seeds for those in attendance to plant. Later, she, Ben, and Ollie spread John’s ashes beneath a Blue Oak tree that rises leafy green atop a slope of Mt. Tam, where in better days John loved to hike and think and admire the view.

The next day, as we walked Stinson’s main drag, we paused in front of the tiny Stinson bookstore that sits across from a bar and grill called the Sand Dollar, a bookstore we learned John dreamed of owning. Sell books by day and live in the apartment above by night. Somehow I never knew, but that’s how John hoped to spend his golden years. I’d wager he read nearly every book in that store, but life got in the way. In his early fifties, John developed a bad back, had a couple of failed surgeries, and spent the next twenty years struggling to adjust to the often debilitating pain that resulted. His dream was deferred, as so many are. Though this makes my heart ache, I’m glad to know of it. It helps me better understand the brother I loved.

Home now, I can hardly wait for my poppies’ spring bloom. And I’m grateful for the new memories of John I’ve gathered, new images of him as a California man. Among these, I’ll cling to two in particular, one grounded in reality and the other a bit of a fantasy: John resting for eternity in the shade of his Blue Oak, a chilly breeze rustling and the mighty Pacific spread before him, and John very much alive, shelving books in his tiny store, his glasses on his nose and his mustache twitching as he chats and smiles and rings up customers. As dusk falls, he turns out the lights, scales the stairs without pain, and enjoys a steak and a glass of wine, the rumble of the surf in the distance and the summer bustle of his adopted town below his window.

Smoke Got in My Eyes

Is wist a word? The OED says not, but I would argue for its inclusion. As an early teen, I was the walking definition of wistful, meaning, quite literally full of wist. Let’s consider possible synonyms … Was I instead melancholy? Nope, the feeling was less gut-gripping than that, yet stronger than longing. Reflective? No way. That suggests an intellectual hankering, which believe me, was years away. But I leaned hard into the wistful in those unsettled days. I was absolutely captive to if not wist, then wistful-ness? So clunky, that word. Plus the emphasis is wrong, less the wist, more the ness.

Shall we delve into a few of my favorite musical selections of the era? There was Carole King’s “Too Late Baby,” and Jimmy Buffet’s “Havana Daydreaming,” and for sure James Taylor’s “Fire and Rain.” Wist, wist, wist … And let’s not forget “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” a remake by the Platters that was an oldie even in my day. I adored it ne’ertheless. I distinctly remember, after a date that went poorly, meandering up my darkened hallway to my father’s study to spin it on the family turntable. Certain I would never date again, I slumped to the window and stared out at our front lawn, moonlight in the weeds. I may have actually shed a tear, so wrapped up was I in my manufactured teenaged angst.

Yet these numbers pale one and all beside the song that gave perfect voice to what was bottled up inside me, a little ballad by the soon-to-be forgotten group, Looking Glass—

Brandy, you’re a fine girl, what a good wife you would be, but my life, my lover, my lady, is the sea …

Is it regret I hear in these lines? Does regret equal wist? No, not really. At least regret is not precisely what “Brandy” evoked for me. It certainly wasn’t sorrow—what did I know of sorrow at age fourteen? But each time my radio played that quick guitar twang, then the riff on the keys followed by “doo doo ‘n doo doo,” my belly quivered and my heart swelled. I would crank up the volume and sing along with great gusto. And no verse bewitched me more than the last: At night, when the bars close down, Brandy walks through a silent town, and loves a man who’s not around …

Oh, the heartache! The delicious pain! This woman, this lovely barmaid, strong and independent yet imprisoned by love for a sailor she could never have. Even now I can feel it, the … the … the wist, for heaven’s sake! One refrain and I’m a skinny girl with long stringy hair who longed for curves ample enough to attract the one swaggering boy everyone yearned to make out with. Yep, there I stand in the dark corners of a fellow middle schooler’s smoky rec room while my friends, maybe a few enemies, roll around on the couch or slow-dance to “Stairway to Heaven.” I lean against the wall, less flower than sprout, and shut my eyes so that I might better conjure, and draw strength from, my precious Brandy—footsore, coins in the pocket of her apron—as she lays that whiskey down. Looped around her neck of course is a braided chain made of finest silver from the north of Spain. And it bears the name of the man Brandy loves! A man (her sailor!) who brought gifts from far away but made it clear he couldn’t stay.

How silly I was, a silly girl looking for love in all the wrong places. Unless maybe, just maybe, what I really hungered for wasn’t puppy love, or even romance. Maybe I couldn’t get enough of “Brandy” because of its poetry–a stretch, sure, but with apologies to any real poets out there, bear with me. Pop tune it may be, but the lyrics and the melody blend perfectly to create a certain mood (right?). A mood, I believe, that reflects and heightens the emotion its songwriters sought to convey. At the very least there’s this: Perhaps in those confounding years of my youth, I longed–without realizing it, mind you–for a sort of experience that was as yet out of my reach. As she pulled beers and served those sailors as they talked about their homes, Brandy took me with her, to that faraway fishing village by the sea where a spunky young woman could make it on her own (albeit without love). The lyrics, the harmonies that bolster them, rustled up in me not only the wobbly ache of the teenaged crush, but the exhilaration of finding oneself in an unfamiliar place or situation, the joy touched with loneliness that solitary travel, for example, can trigger, and that several years on, I would come to know myself, and to treasure.

So maybe my pre-pubescent self, my mind (my soul?), stood in awe of the power of the artist, the power to make words and rhythms work so effectively in tandem that they forge emotion out of air. Magical thinking? Could be, but to believe it, that at some level even then I hoped to imprint others with words the way Looking Glass imprinted me, gives me great solace.

“Brandy,” to conclude, has staying power. When a band cranked her up during a wedding reception I attended recently, I embarrassed myself by jumping and spinning (partner-less), circling my arms overhead and shouting every last syllable at full volume. The crowd of mostly twenty-somethings around me danced and sang along, too, if with slightly less passion.

All wist and wistfulness aside, “Brandy” continues to transport me, as all good art should. A couple of her introductory notes sound through my Pandora app, and I’m right back on that western bay, where I can feel the ocean fall and rise, and see its raging glory.

Note: This post grew out of a writing prompt my friend and fellow writer, Mai Al-Nakib, shared with our beloved writing group in June (thanks Mai!):

“Think of a song that meant something to you as a teen … Why did it mean so much? Does it still? Explore it in writing… “

If you have a second, drop in a comment below about a song you once loved that can still bring a little lump in the throat. I’d love to hear from you! And be sure to check out Mai’s latest book, An Unlasting Home, a gorgeous and expertly researched multi-generational novel: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/an-unlasting-home-mai-al-nakib/1139827261

Home at Last

Some of you met Mary Darian in “I Am Mae Mobley,” one of my early posts here in My Mother’s Attic. In part an outcry against an upsurge in race-related killings during the summer of 2016, that piece is at heart a tribute to Mary–the woman who helped my mother rise to the Herculean task of raising six children. Since I launched this blog, Mae Mobley continues to garner far more views than any other Attic post–testimony to Mary’s captivating character. In that earlier piece, I lamented that during the two decades Mary worked for our family, I failed to learn much about her life. I vowed then to make amends for this, to reach out to Mary, though I was more than a little nervous about cold-calling after so many years of silence. I might have known that was a waste of emotional energy. In the years that followed, in spite of facing one personal challenge after another, Mary shared detail after detail about her story, and more broadly, her family’s story, which to her were one and the same.

One morning not too long before the pandemic hit, I went to see Mary at the nursing home where she’d recently moved. Her room was small but comfortable–a sink and closet against one wall, a twin bed at the center, a broad window at the far side, the ledge below crowded with photos of her grand- and great-grandchildren. Mary’s devoted daughter, Lou, had a bird-feeder installed just outside the window so Mary could enjoy sparrows and robins and fiery red cardinals as they flitted about. By this point in her life, Mary was confined to a wheel chair, though I was soon to learn that in her case, confined did not apply.

I breezed through the door a little earlier than usual to find no Mary in sight. I heard a scuffle on the far side of the room and stepped closer. She had wheeled herself into the narrow space between bed and radiator and crouched low over her knees, her head nearly hidden between the bed and bedside table.

“Mary?” I asked, trying to control the worry in my voice. “Can I help?”

“Oh!” she said, her voice bright with enthusiasm as she looked up. “Angel Face!” (the pet name she coined for me as a baby). “Come on over here!”

I did just that. Mary craned about and reached her long arms around my neck. That’s when something shiny flashed in her lap–a long, thin metallic tool.

“Just give me a minute …” she said, ducking head under table again. “While I find my Puh …”

“Here, can I get it for you?” I asked, though I wasn’t sure what I was looking for. Her paper? Her pillow? I tried to maneuver between wheelchair and radiator but the space was tight, the bedside table happily cluttered–a card illustrated in blue crayon, a tub of Vaseline, a small glass vase filled with Alstroemeria, a stack of word puzzle books and a red leather Bible, its pages well-thumbed.

“What is it you need, Mary?”

No answer, just more poking at that shelf.

“Ah, here it is!” she cried at last. Turning, she sat up straight, her expression devilish and triumphant. “My Ponds!”

She held out the stick, which I then could see had a grip handle at one end and a sort of claw at the other, not unlike the mechanism in that arcade game in Toy Story (The claw is our master … ). Caught firmly in Mary’s claw was a jar of Ponds cold cream, same pale green cap and tulip logo as the ones my mother used to keep on her vanity table.

With easy dexterity, Mary twisted open the jar, scooped out a finger full, and chatting all the while, began massaging the silky cream into her still-smooth complexion. Her task complete, I offered to return the jar to its shelf. She laughed, waved me away, and did it herself, metal claw re-extended. Then she nabbed her hairbrush from the drawer, dropped it in her lap, and wheeled over to the sink. One of her feet–slightly swollen–nearly collided with the corner of the bed frame as she went.

“Mary, your leg–is it ok?”

“Oh that …” she mumbled as she set the hairbrush at the edge of the sink. “Some kind of blood clot in that old leg.” Then she plucked a cloth from a towel rod, wet it generously, and ran it across her short thick curls before brushing them out.

“Ok, now …” she went on, patting her head and smiling at my reflection in the mirror. “That’s better. I never know what it’ll look like in the mornings.” Then guttural laughter as she spun her chair around to face me. “Now tell me … What have you been up to?”

I gathered my thoughts, but before I got a word out, her eyes flew open wide and she cried, “Wait a minute! … I forgot my teeth!”

With that, and without a wrinkle of embarrassment, Mary spun back around, tugged a set of dentures out of a cup and slathered them with toothpaste. While she gave them a sturdy brushing under the faucet, I marveled at the independence, the lack of self-consciousness, and the serene acceptance of the time-consuming rituals of growing old that she possessed.

“Your mama liked Ponds, too,” she mused. “You know …” She paused and turned to me, that devilish smile restored. “She may have been the one who got me started with it!”

Whether this was true or its inverse–that Mary actually introduced my mother to Ponds–didn’t matter. This was a habit they shared, one I hadn’t known about, and something soft padded into my heart. Not a visit passed between us that Mary didn’t turn our conversations back to my parents, or one of my siblings–to those days she was part of the everyday workings of our busy household. She loved especially to wax on about my mother’s expertise as a seamstress, but then she’d been doing this since my summer camp days. Your mother made a white jacket for her new formal gown with shells around the midriff … she penned in a letter she sent off to Camp Merrie-Woode. Wow! When the lady moves, she gets momentum and never stops … Then, one of her witty after thoughts–I think she’s going to wear her sexy red sandals.

Back then, ten years old and homesick, I likely cried to read this, but it was a good cry. Mary was enfolding me from a distance into the home life I loved. I understand now that during our recent visits, she was doing much the same. Her smiles, her laughter, her stories, were keeping my mother, my father, in short, my childhood alive. She did me as much good–no, probably more–than I did her.

Though she lost her mother very young, Mary was eager to share her father’s story, too. In the 1920s, when he was hardly more than a child, Jimmie Lee Cochran worked the cotton fields of Hurtsboro, Alabama, where he lived on a farm with his mother and grandmother. In 1939, when Mary was four, Jimmie Lee came within an inch of being lynched. After a narrow escape, he managed to slip away to Atlanta, where he built a long career with Southern Railway. More importantly, a decade later Mary’s father brought her and her younger siblings to the home he’d built–literally built with his own hands–for his family. The twists and turns of Jimmie Lee Cochran’s story, and Mary’s alongside, paint a shimmering picture of courage, devotion to family, and perseverance. It’s a story that could fill a book. Maybe someday it will.

Born in 1935 in Hurtsboro, Mary Cochran Darian moved on from this world on April 18th, 2023. She worked those Alabama cotton fields herself before graduating from Atlanta’s Booker T. Washington High. She married her sweetheart, Lewis Darian, and after twenty years with our family moved on to an administrative career at Crawford Long Hospital. Through it all, Mary took care of people–her four children, her physically disabled brother, her neighbors and grandchildren, her church family (to them she was “Mother Darian”) and me and … well, the list goes on. Her family held a “Homegoing Celebration” last week at her beloved church. The service left room for sorrow but had joyful music aplenty and tributes full of love and hope meant to speed Mary along on her journey to the place she firmly believed was her true home. I think everyone who spoke of Mary mentioned that infectious smile that so warmed me during our visits in her last years. I’ve mentioned the knack Mary had for helping me laugh away my little girl challenges and preteen angst. Her ability to smile and laugh herself through the many trials of aging was to me more remarkable. My mother had her strengths, but facing old age with grace was not one of them. She raged against the dying of the light, and though there’s something to be said for that, the way Mary kept her spirits high in spite of the slings and arrows fortune tossed her way not only eased her days, it lightened the hearts of those who cared for her.

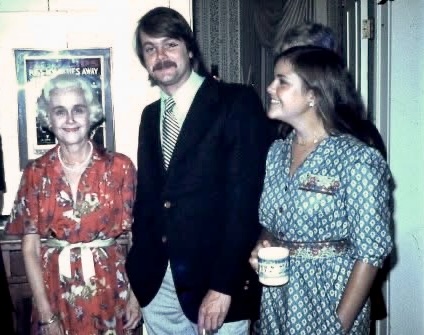

The pastor who gave Mary’s eulogy asserted that her smile set an important example. If you love God, he suggested, the least you can do is smile for the world to see. Mary’s resting face was a smile, a natural one, broad and vibrant in a way that said, Watch out because here comes a laugh, a big one straight from the belly! The photo below offers proof. I can hear my brothers and my father laughing with Mary even now.

The cover of Mary’s Homegoing tribute booklet features a couple of her favorite phrases. “I expect a miracle every day,” reads one of them. For those who consider miracles to be only raising the dead or turning water into wine, this may sound like hyperbole. Like the wisest among us, Mary knew that the simplest things could be miracles: The touch of her first great-great grandchild settling into her lap; the familiar taste of the meals Lou prepared at home and brought to her room; the right to vote safely and the freedom to shop where she pleased and sit at the front of the bus (freedoms she had to wait until age thirty to enjoy); the weekly Bingo games (she won a lot) with other residents in the nursing home common room; a skittish bluebird in the morning sun, darting close for a nibble from her feeder before the pushier birds moved in.

Miracles every one, just as Mary was to all who knew her. She is home now, flights of angels singing her to her rest.

A Tale of Two Cousins

During a late sweep through the dark corners of my mother’s attic, I stumbled upon a moldering shrine to one of my paternal great-aunts. Louise Bickers, a.k.a “Weezer,” was a feisty single woman whom I loved like a grandmother. With affectionate if drowsy interest, I dragged over a rickety wooden stool and dusted off her leftovers—stacks of limp letters, photos with curled edges, family trees scribbled on yellowed paper, and a decomposing shoebox of daguerreotypes.

Stumped? So was I. An early form of photograph produced by “fuming” mercury vapor onto silver-plated copper, the daguerreotype was introduced in 1839 and became obsolete by the 1860s. The 1860s! And there I sat, a hundred and fifty-plus years later, with several in passable shape. I ran my finger along the hammered tin frames, eyed the elaborate clothing, the formal, sometimes severe gazes. Where did these people—certainly family—live? What did they do? My curiosity piqued, I tucked the least fusty samples into a fresh plastic bin beside far too many of Weezer’s letters and photos and family trees, and moved on.

During the pandemic’s endless, vacant shut-in hours, I fetched up those family trees, rebooted my Ancestry.com membership, and typed in name after name. It was fun, by 2020 standards, learning how to create profiles for my long-lost blood kin and search for relevant documents and photos. When a grainy image of one of my great-great grandfathers popped up, I knew immediately it was—you got it—a daguerreotype. I fished out Weezer’s frames to compare and contrast. None of the faces matched exactly, but they favored, as my mother would say.

At once piercing and playful, my second great grandfather’s gaze seems especially, hauntingly, familiar. Born in 1825, Thomas Blake Bourne descended from a long line of tobacco planters in Calvert County, Maryland, a leg of land that kicks out into the Chesapeake Bay. The Census of 1850 valued his property at $2,500, equivalent to about $150,000 today, making his a healthy if small farm for its time. I can’t pinpoint the farm’s exact location, but odds are it was on or near Eltonhead, a tobacco manor along the instep of the county’s watery foot, tracts of which had belonged to Bournes since the late 17th century.

A city girl, I smiled to picture my great-great grandparents, Thomas and Margaret Louisa, living their quaint, rural 19th century lives. Soon a marriage record surfaced from May of 1848, a photo of Thomas’s gravestone, the inscription honoring him as “… a devoted husband and father, true to his friends and his country,” and a certificate proving that his maternal grandfather, Colonel Joseph Blake, fought in the American Revolution. Cool. I’m a DAR. I felt all rosy with pride. Then something else, less than quaint, caught my eye—a Slave Schedule, an appendix to the 1850 Census in which enslavers identified their “human property,” not by name but according to age, sex and color. I blanched, my ancestral pride dissolving as I counted the tick marks beside Thomas’s name: an even ten, six black males and four black females between the ages of six and forty-five.

I attached the Slave Schedule to Thomas’s profile and clicked back to his daguerreotype. That playful grin … might it be more a cunning smirk? My forehead heavy in my palm, I called my daughter in New York.

“We are from the South, Mom,” she said, unsurprised.

“But your grandfather came from humble roots,” I argued. “And Maryland’s hardly the South …”

“I know, Mom,” she said gently, knowingly. “But even small farmers enslaved workers back then.”

Which I knew, but this was our family, a whole different ballgame. I hung up and returned, dull eyed, to my laptop screen. Lined up in the right margin, I noticed tiny circular photos I’d missed before, profiles of other genealogists who’d saved Thomas Bourne’s image. I hovered over one, then another and another, and a pattern emerged—many belonged to people of color. What’s more, the family tree associated with each profile included a common ancestor, a man named Louis H. Bourne.

With clammy fingers, I typed Louis’s information into the Ancestry search engine. My first hit was the Census of 1860, which lists Louis H. Bourne, born 1830, as a “mulatto” head of household and farm laborer in Calvert County. More hits revealed that by 1880, Louis and his wife, Margaret, had purchased over thirty acres of land and settled down to farm tobacco in Island Creek, a breezy community along the Patuxent River that lies about fifteen miles from where Thomas Blake Bourne lived with his family.

Or used to live. In 1855, amid rumblings of the war to come, Thomas had moved his household—including three children and at least nine enslaved persons—across four rivers and the Mason-Dixon line to a manor house near the James River in Virginia, a state he surely wagered would prove friendlier to his future as a planter. Eight years and three children later, Thomas enlisted to fight for the confederate states. He was thirty-eight. Around the same time, Louis H. Bourne, thirty-two, signed on with the Union Army. And so it was that second cousins, as I believe they were, took up arms against each other in a war rooted in misconceptions and greed. Were Thomas and Louis aware of this? I suspect so. It was a much smaller world then and Thomas still had family aplenty in Calvert County. Both men survived, though my great-great grandfather would die suddenly ten years later, the youngest of his nine children only eleven years old.

As intrigued as I was conflicted, I reached out to a few folks whose trees included Louis Bourne. Responses were scarce, but eventually I heard from Florencetine “Tina” Bourne Jasmin of Baltimore County. I hesitated–what right did I have to barge into her life?–then dove in and wrote to her that we could be related, somehow, through Louis Bourne.

“Oh my gosh,” Tina responded. “I’ve been hoping to find someone who might know something about my great grandfather!!!” Smiling again, I shared a little about my family. Tina sent photos of her son and daughter and grandchildren. She told me Louis Bourne had remained—thrived—in Island Creek until his death at seventy, as did many of his children, and some of theirs, and theirs and theirs right up to the present. Louis and Margaret had eleven children, among them trailblazers who stared down the fetters and hostilities of the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras. One of their sons, Ulysses Grant Bourne, was among the first black physicians to practice in Frederick, Maryland. A grandson, James Franklyn Bourne, Jr, was the first black judge to serve on the district court for Prince George’s County. Quite a legacy, an improbable triumph in fact, and this was only the beginning.

At some point, I told Tina I regretted the unspeakable abuses my ancestors had visited on hers. “This history is beyond our control,” she mused. “I want to believe our ancestors are pleased with us for trying to reconcile our past.” Awed by her tolerance and wisdom, I thanked her and we dug in, working to make sense of our family ties. Tina quickly shared her best clue–a digital copy of Louis’s death certificate which names his mother as “Gracey Mason,” and his father as “James Bourne.” James Bourne? Thomas’s father, my third great grandfather, was named James. But then so was his oldest son, and his first cousin, James Jacob Bourne. Which James fathered Louis? And did he enslave Gracey Mason and the son they shared? Hard to know. A pair of 19th century Calvert County courthouse fires destroyed wills and bills of sale that might have given us proof.

We called in help. Tiffinney Green of Baltimore, Delma Bourne-Parran and Patrice Evans of Prince Frederick, and another cousin in California, all descendants of Louis Bourne, joined our search. The emails flew. We shared trees, unpacked oral history. Hoping to discover shared DNA, we spit in vials, waited, and waited some more.

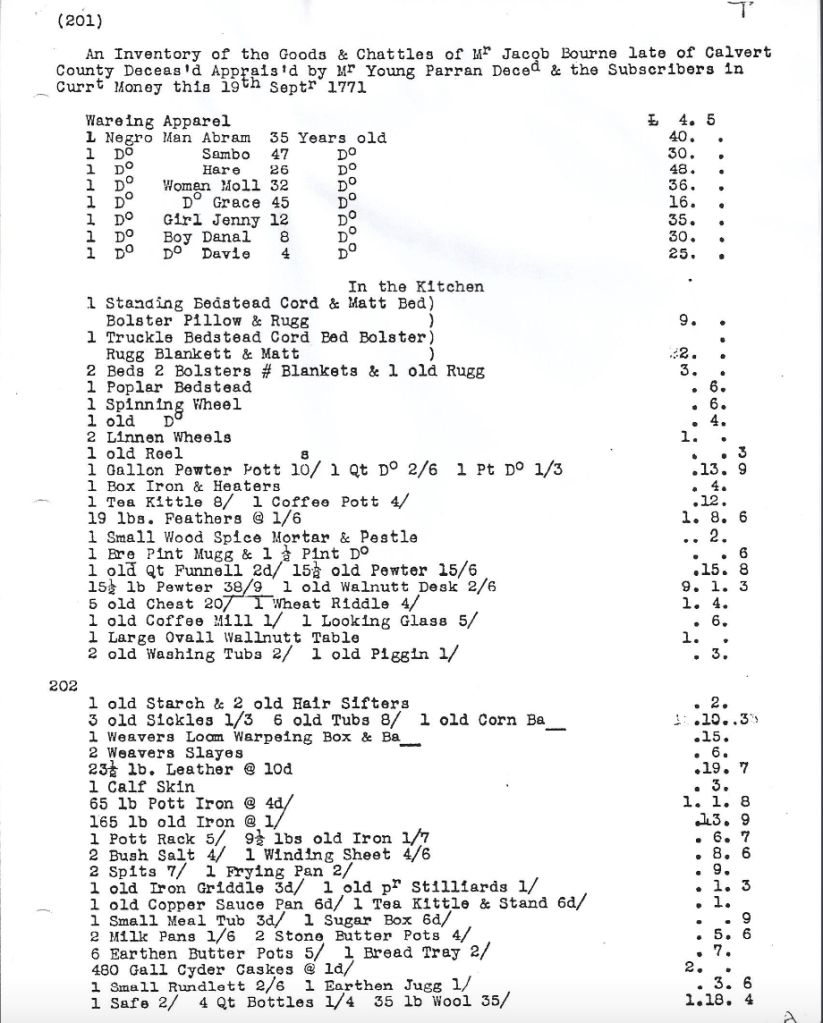

The results: Delma, Patrice and Tiffinney each match with at least one of my distant white Bourne cousins. And the kicker–Patrice’s sister and I share DNA. Heartened by this proof of our kinship, we analyzed and drew charts and at last wagered that James Jacob Bourne (1791-1850), an enslaver of twenty-two, most likely fathered Louis H. Bourne. This means our common direct ancestor is my fifth great-grandfather, Jacob Bourne (1721-1771), whose will survives with a full inventory attached. In the same figurative breath as a tea kettle, three old sickles, and the spinning wheel in the corner, Jacob names Grace, age forty-five, as one of several enslaved people to be “gifted” to his sons. Might this Grace have had a granddaughter who was passed down the line to James Jacob? It was common after all for baby girls to be named for a grandmother.

Due to those courthouse fires, for months we had little else to go on. Then Tiffinney found a Grace Mason, born 1807, listed in a Calvert County registry of Free African-Americans in 1832. She lived with a Hannah Mason, age forty. A Louis Mason, age two (just Louis Bourne’s age), also appears in the registry and seems to have been part of Grace’s household. Grace and Louis Mason then disappear. Free people of color were often servants in households that enslaved others, and our hunch is that Grace Mason worked for James Jacob Bourne. Maybe at some point, say when Louis was a child, James took in Grace and their son, maybe even enslaved them in some sort of twisted effort to control them. Did Louis Mason then become known as Louis Bourne? Did James Jacob later free his son who should have been free all along?

We’ll likely never know the full truth. The fact that Louis shows up in the 1860 Census means he was a free man well before Maryland officially emancipated its enslaved. Hannah Mason, the woman listed alongside Grace in the 1832 Registry, provides another clue. Louis’s 1860 household included a Hannah Mason, age seventy-four. Though the years don’t quite match up, they’re close enough for that era to suggest that Hannah was Louis’s grandmother, and that her daughter–Louis’s mother, Grace–died young.

Unless James Bourne sold Grace off.

“I pray that was not the case,” Tiffinney wrote to me.

I pray so, too.

Much work remains. Most of my family lines run back to the colonial era, where other fraught relationships lie in wait. Tiffinney and I have DNA matches in common that suggest we may also be kin through my Mattingly side, and I’m in touch with another young woman directly descended from Colonel Joseph Blake. Looks like the Colonel’s son had his violent way with her third great grandmother.

In May, my sister, JoJo, and I visited Calvert County. We researched alongside Tina and Tiffinney, and after, the four of us gathered for dinner with Patrice, Delma, and Marietta Bourne Morris, who still lives in Island Creek. We bored each other with family stories. We laughed over wine and margaritas. Humbled, JoJo and I accepted the kindnesses these women offered. Strong one and all, they overlook with seeming ease the troubled origins of our relationship and accept us as family. I’m proud to call them cousins, hopeful that Louis and James Jacob, Thomas and Grace Mason and my great aunt Weezer are indeed pleased.

Moving forward, I’m not naïve enough to expect from others the open-hearted welcome I’ve received from the Bournes. It’s nothing I deserve. One thing seems certain—this is not a tale of two cousins. It’s a tale of hundreds, thousands—dark-eyed and green and blue; blonde, red-haired, brunette; Irish and Bantu and Latin, Nigerian and Welsh and Congolese. Our skin shines ebony and alabaster and every hue between, and our cells quiver with the tangled threads of those who came before us, our human race.

Postscript: If this sort of research project interests you, message me below or through Facebook. I’m happy to share tips and links to resources. There are many!

Lady Nona

Happy New Year! What a year it’s been. Like everyone else, I welcome 2021 and the hope and possibility it brings (yesterday’s horrific events in DC notwithstanding).

It’s been a while since I dipped in here to post, and I believe the last time I did I declared my intention to abandon my Attic blog altogether. Well, here I am again, but for something a little different. Today I share a short story, one I’d about given up on seeing published until The Dead Mule School of Southern Literature kindly included it in their January, 2021, issue. I’m grateful to the Mule. It’s a wonderful issue, by the way, in a lovely journal. You can check it out here: https://deadmule.com/

The setting of “Nona’s Gift”–a college town on a football Saturday–springs from my memories of UNC-Chapel Hill in the early 1980s. My late mother with her snobbish tendencies and ladylike grit inspired the character of Nona herself. It seems only right, then, that this story have a place in “My Mother’s Attic.”

Hope you enjoy!

Martha Payne: Fiction: January 2021

Nona’s Gift

Nona reaches for the red beret hanging on the coat tree by her front door, and misses. Despite the ache in her joints, she rocks forward on the balls of her spectator pumps and gives it another whirl. The beret slips successfully off its hook. It’s a good Irish wool, soft. It warms her ancient fingers. Nona grips the beret gratefully as she gathers up her purse and walking stick, locks her door and totters up the carpeted hall of what her daughter calls “the home,” though it’s anything but.

The elevator, thank Jesus, Mary and Joseph, is empty. Nona steps in, takes a sniff. Urine. She rolls her eyes. She’s had it with old people and their sloppy hygiene. Ground floor. Nona braces for the painful jolt as the elevator hits bottom. Then she settles the beret on her silvery head, checks the mirror on the back wall, and adjusts so as to center the beret’s rhinestone brooch above her left brow, the way she likes it.

Outside, all is crisp and blue and breezy, perfect weather for the tailgaters who will soon be making merry at the stadium parking lot. To think of their Solo cups and onion dip makes Nona thirsty. She picks up a little speed, hoping to outfox the light at the corner of Magnolia and Main. It flashes yellow before she’s halfway there and she slows again. Not to worry. If they’ve run through the single malt by the time she arrives, Nona feels sure young Stuart will find her a decent glass of Dry Sack. She squints against the Carolina sun and steps to the curb. A crowd gathers behind her. To her left, a horn shrieks. Breathless, she clutches her purse against her bosom. Through a cloud of exhaust she watches a jeep sweep around the corner, its body splashed with paw-prints. Lengths of red and white crepe paper whip from its roll bars, and three—no four—barelegged girls balance on the running boards. Swaying left, then right, they shake pompons and cowbells and shout—GoCats! Numberwan!

Her small feet splayed for good balance, Nona clucks her tongue and shakes her head. Then a thought, a terrible thought as young bodies jostle past, bumping her hips, her bony shoulders. Her heart aflutter, she opens her purse. All darkness. With trembling hand she fumbles past her wallet, a dusty lipstick tube, a blue lozenge and several loose aspirins and ah! There it is, beneath the glare of her compact. She hasn’t forgotten: Stuart’s gift, a box the size of a baseball wrapped in gold and tied with matching elastic ribbon. Nona touches a bent finger to the cool paper, lets go a sigh, snaps the purse shut.

From a few blocks away comes drumbeat and blast of trumpet. Nona trains her eye on the signal across the intersection. It shines green. Shouts, chatter, the thump of a heart, her own. She wavers, her softly furrowed cheeks coloring beneath twin smears of crème rouge, then rights herself and steps off the curb, swollen knees and narrow hips cooperating with a grace she’d thought long gone. The electronic hand ahead flashes three times then becomes the number nine. Nona lowers her gaze and moves along, her cane ticking off with each measured step the manic neon countdown—six, five, four …

“It most certainly is not a cane … ” Nona mumbles to the image of her daughter’s face that rises in her mind, stern and round as the moon. “A proper walking stick this is, been in the family since … ” She wets her lips and raises her voice, but Nona forgets exactly who it was, which of her grandfathers, or great-grandfathers, whittled the stick, carving it out of mountain laurel sanded soft as mink. “Well, I don’t care who whittled the thing. It’s positively not a cane, as anyone with half a lick of sense can see …”

At the opposite curb, Nona pauses beneath the signal light, fingers the khaki piping at the collar of her peach-hued St. John’s knit, and eases up one foot, then the other. Her pale crooked fingers bear down on the walking stick’s handle and she just manages to scale the curb. Nona resents the stick’s handle, an ugly rubber affair Melinda’s husband attached, poorly, the day they moved her out of the house (an English Tudor on an acre lot) that she and Mr. Snyder saved twenty years to build. “Part of the deal, Mother,” Melinda announced while the glue dried, big bulbous globs of it that overflowed the handle’s edge, spoiling the walking stick’s lines altogether. “We retrofit that handle for safety, Missy, or you stay put.”

The sidewalk is moving! Nona plants her pumps at hip width. Then she sees—or hears—that it’s only music, rock music playing so loudly through the open windows of the columned house on the corner it vibrates deep into the earth and back up again. A plastic disc sails past Nona’s shoulder, then ziiiiing-pop! Something flies out a window and splats against the ancient oak tree to her right. A boozy mist falls over Nona’s face, mingles, glittery, with her finishing powder.

“Sorry, Granny!” screams a youthful voice through a window. Then, a chorus of deep-throated laughter.

Pabst, Nona sneers, licking her lips and feeling all the more proud her grandson chose to pledge at the fraternity down the block, where for Game Day Brunch, the brothers serve sausage-cheese casseroles with pecan pinwheels and drink the way they did in her day. Bloody Mary’s, mimosas when it’s hot, whiskey straight up. They stock beer for those who must have it, mostly the climbers from the eastern counties, but serve it discreetly from a cooler on the stoop near the service entrance.

It’s the front door for Nona, a tasteful Colonial with a modest transom. Once she’s scaled the porch steps, she raps the door with the rubber pad of her walking stick. Inside, a television blares: “Wear Nike and sweat like you mean it!” Nona knocks again, harder. Nothing. She shuffles back a step, then another, and lifts her walking stick high, aiming for the doorbell. Her shoulder creaks and her wrist downright wobbles with pain but ding-dong! She’s done it. She can just hear the chime above the din.

A young coed—slender, doe-eyed, blonde—swings open the door. Her skirt is too short, her top too skimpy.

“I’ve brought something for Stuart,” Nona declares.

“Stuart?”

Nona gazes at the blonde through rheumy eyes. “Yes. Stuart Bridges, a third year. Come January he starts his term as president. Elected by unanimous vote. Today is his birthday.”

“Who is it, Tink?” A voice from inside—Tink? What kind of a name is that? The voice is not Stuart’s, but Nona recognizes it.

“Uh, um, a Missus … ?” The blonde gives Nona a look she doesn’t like. Pity-full. Who needs it.

“Tell him it’s Mrs. Snyder,” she says, raising her voice, along with her chin, up and over the relentless music. The bass notes tremble, not unpleasantly, up her legs and spine.

“A Mrs. Snyder!” calls Tink. She smacks something, gum maybe, or cud, and her eyes crinkle up in a smile. “Looking for someone named Stuart? Says he’s her, uh …” With a cheeky wink, the blonde leans close and whispers. “Grandson?”

Nona nods, sniffs. Dime store perfume. “Stuart Snyder Bridges,” she declares, nose upturned. “After my late father-in-law, Stuart Jefferson Snyder.”

“Her grandson!” calls the blonde, smacking harder. “Stuart? Says he’s a junior?”

“Thanks Tinkerbell!” A broad-shouldered young man with glossy hair slides a hand around the blonde’s hip and moves her gently aside. “I’ll take it from here.”

The blonde smiles, gives a final triumphant smack, and trots away, ponytail bouncing.

“Hi there, Mrs. Snyder. Glad to see you sporting our team colors today.” With a winning smile, the young man gestures at Nona’s beret with firm fingers that brush the brim ever so slightly. Nona grins, hesitant but proud.

“Stuart had to run out …” the young man goes on. “Uh, for more mixers.”

Her face pinched, Nona studies his eyes, his jaw line. She tilts so close she can feel the silky hairs along his forearm.

“Now John, why didn’t you say that was you?” she says. Flushing with pleasure, she lowers her head and starts across the threshold while John, whose name is Cliff, steps aside to let her pass.

“I’m sorry, Mrs. Snyder. We weren’t expecting you so early. I think you’ve been walking faster this season.”

“You think nothing of the sort,” says Nona with a smirk. Walking stick tapping, she makes her way to the living room and sits on the ragged couch. It smells of dog.

“Single malt, neat?” shouts John who is Cliff.

“Splash of soda today. Thank you, son.”

Her purse in her lap, Nona rifles through its fusty depths. She pulls out Stuart’s gift and cups it between her hands. Patient, she watches huge players moving across the huge gridiron on the huge television across the room until John who is Cliff appears again, a sweating lowball in one hand.

“I see you remembered Stuart’s birthday,” says Cliff with a wink. White cardboard peeks through at the corners of the box where the wrapping paper, which once had a sheen to it, has worn smooth and begun to split.

“Why yes I did,” Nona says, and for a moment all her aches and worries soften. “Thank you, John,” she says, and extends her hand.

“Yes ma’am,” says John who is Cliff. He grasps her fingers, hands her the lowball and leaves. A deep gulp, and Nona settles in to wait.

In his townhouse seven miles away, Stuart Snyder Bridges, a thirty year-old accountant with a March birthday, pulls his cell phone from his pocket.

“Hello, Mr. Bridges. So sorry to bother you …”

It’s a voice Stuart knows well. A brother, Cliff, if memory serves, though they sound younger every time. “I’ll be right over,” he says.

In the frat house living room, Stuart’s grandmother drains her scotch.

“Would you like another, Mrs. Snyder?” Different voice, different young man, one Nona feels less sure about.

“Don’t mind if I do, dear,” she says nevertheless. “I’m sure Stuart will be here soon.”

“Yes, ma’am, he’s headed back now.”

“Oh, my. Thank you, son.”

Panicked, Nona searches for her purse, which someone has set on the floor. Her foot bumps the patent leather bulk of it. As she reaches down, the hard edge of the gift box presses into her belly.

There it is, Stuart’s gift. She hasn’t forgotten.

Nona relaxes into the soft odorous sofa cushions. Beneath her fingers, the box in its gold paper feels cool and expensive. She can hardly wait for Stuart to see it.

She Who Taught Me to Read

Honestly, I’m not sure this is true, that my mother taught me to read. I recall lying belly-down on a thick-piled prickly rug (an Oriental, as Mom used to call them in the days before we knew better), sounding out words in The Little Engine That Could. But the rug in question covers the floor of my father’s library, and it is my father, crunching numbers at the desk above me, who comes to my aid when phonetics fail and I stumble over a word.

Honestly, I’m not sure this is true, that my mother taught me to read. I recall lying belly-down on a thick-piled prickly rug (an Oriental, as Mom used to call them in the days before we knew better), sounding out words in The Little Engine That Could. But the rug in question covers the floor of my father’s library, and it is my father, crunching numbers at the desk above me, who comes to my aid when phonetics fail and I stumble over a word.

The thing is, “learning to read” involves much more than figuring out a diphthong (“bl” plus “UE” equals blue?!?), or understanding that “th” ends up sounding like whatever it is (“I think I can, I think I can,” said the little blue engine). Learning to read means coming to love the musty smell of an old paperback, the grainy touch of its spine, the voices both lyrical and rational that speak from the pages of any book, even an e-book. Learning to read means finding your proper posture. For my mother, this meant perched with straight back, ankles crossed and feet up, whether tucked, tickly, behind me on the couch or buried under her bedcovers. Learning to read means losing yourself to the story, soaking it in through your pores so deeply that the satisfaction of reaching the conclusion to a well-crafted tale feels not unlike the sensation of discovering someone you’ve long loved from afar loves you back. And when the tale ends, when you must surrender your book’s characters and plot twists and precise lovely language back to its well-thumbed pages, it’s as sweet a sorrow as love lost.

But my father. It’s not that he didn’t read. Daily reading was part of the routine that sustained him. His day at the office complete, the dinner dishes rinsed and racked, he carried his Wall Street Journal and the Atlanta papers to his armchair in our family room and settled in. He read his papers pretty much cover to cover, but he wasn’t much into fiction. At one point in late middle age he became enamored with Ferrol Sams, a Georgia novelist whose most successful book, Run with the Horsemen, told a coming-of-age story about a young boy growing up during the Depression, much as my father did. Other than that, I don’t remember a single fictional title in Dad’s lifetime bibliography. He may have shored me up with the fundamentals, provided the scaffolding for the life in words I would build, but it was my mother who proved true the adage, Children Do What You Do, Not What You Say. Mom read everything, everywhere: den, kitchen, bedroom; trains, planes, automobiles; mountain cabins, hotel rooms, beach.

Yesterday was her birthday, number 101 were she still with us, and with COVID19 running roughshod over our world and everyone in it, I have more time to read. It’s one of the things that helps me stop obsessing (did I wash my hands after touching that banister? Wipe down that counter where my son just scarfed down a sandwich? Did I, did I, did I?) I’m glad, in a way, that my parents aren’t around during these troubled times. My mother, as my sister reminded me this morning, couldn’t abide talking about one’s health, or illness in general (what else is there to talk about now?). And my father lost his mother to the 1918 Flu Pandemic, the only other health crisis in modern history to grip the entire planet as ruthlessly as COVID19. Dad always claimed he couldn’t remember his mother’s illness or death. He was only four at the time, but I fear some long-repressed and terrifying images might have resurfaced for him, were he around to try and survive this scourge.

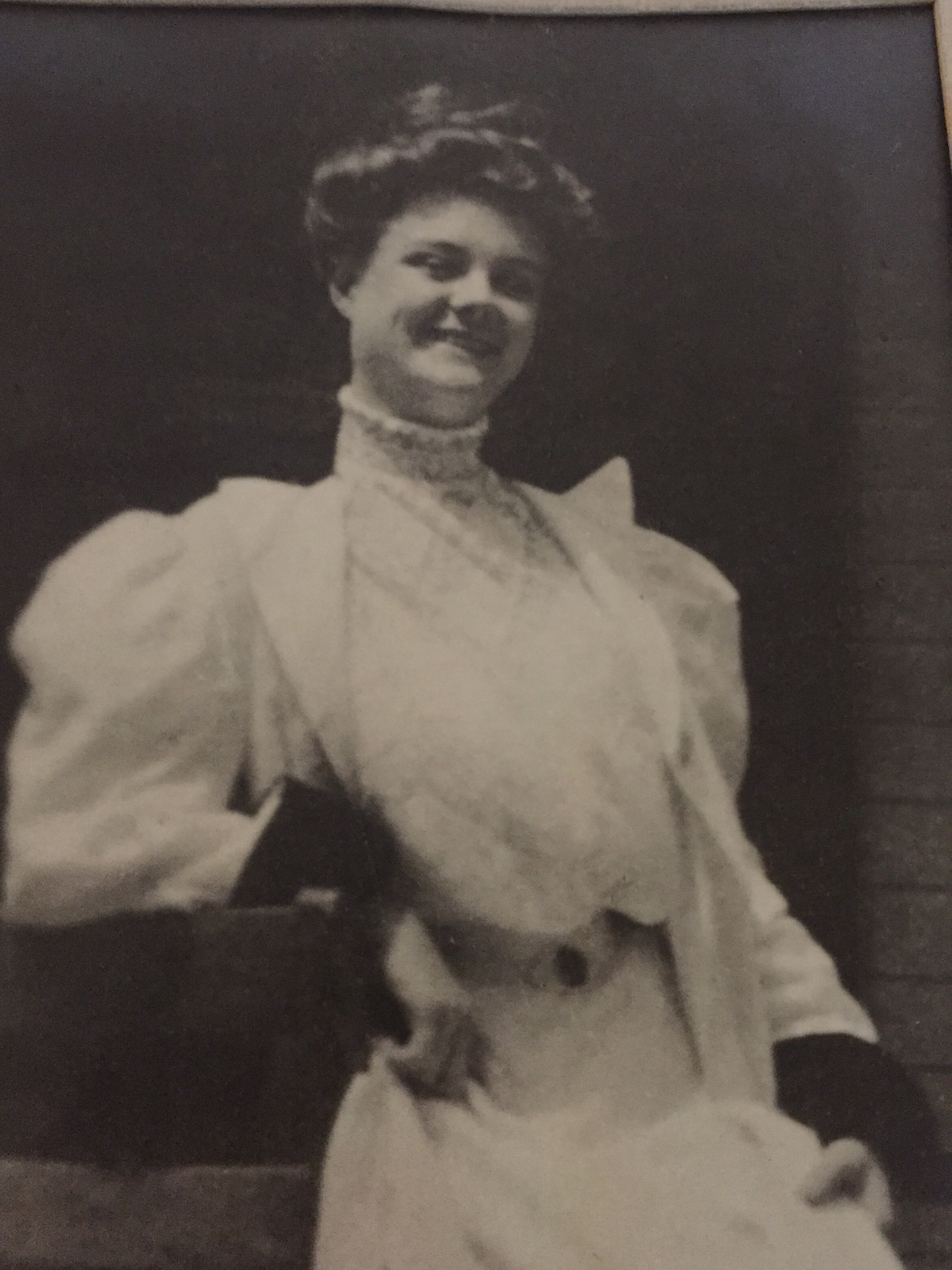

My grandmother Mattingly was a lovely woman, as you can see here. She died, pregnant with her fourth child, at age thirty. Unlike COVID19, the 1918 pandemic killed mostly strong young adults. Though I never knew her, I miss my grandmother somehow, and always have. With all this idle time on my hands, I miss my father, and especially my mother, during this, her birth week. The less we’re occupied, the more strong emotions rise to the surface I suppose. And though it seems wrong, selfish to speak it, I miss getting together with friends. I miss eating out and going to movies and plays and damn it, it’s spring. Of all entertainments, I miss baseball the most.

We–that is those fortunate enough to have so far avoided the virus–have lost something we desperately need: camaraderie, breaks to the routine. But I have what Mom left me, a love of books to help pass the shut-in hours. And I’m most grateful.

Centennial

All week, I’ve been noodling over a proper way to honor my mother on this March 21, 2019, the day she would have turned 100. I hate to repeat myself, or post photos I’ve likely used before, just because for my family this is a noteworthy day. But it does seem significant, the centennial. When early this morning, before my second cup, my daughter launched a group family text from New York, I thought, hmmm, she nailed it, and with little more than a string of emojis. Who needs words? Emma gives a crisp and warm tribute to “Joe,” the grandmother she respected and adored.

Then again … for those who still love words the way Joe did, perhaps a brief concordance is in order: Not exactly an angel in life, my mother, a devout Roman Catholic, certainly wears the loveliest of halos now, in one form or another. A woman worthy of swirling hearts? Absolutely. A charmer who loved to dance to the likes of Glenn Miller, she had her share of romances and enjoyed them every one, but once she settled down (at 22 no less), she was a loyal and caring partner to my father for 63 years. A superstar? Yes, Joe was, if a quiet one, as the characters that follow the star aptly suggest. Flowers … give her an old cut glass vase and she could bring out the best in simple back yard blooms. And, ah the little blue dress. Had she lived in another time or birthed fewer children (i.e. me), my mother had a shot at being the next Dior. Her sewing machine was her creative outlet and her family’s delight, as my sister and I and Emma herself can attest. At 81, Mom created for her a flower girl dress to wear in my nephew’s wedding that was elegant and sweet, just the thing for a six-year-old .

Next a crown … Was Mom the Princess to my father’s Prince? Indeed she was, bejeweled and beloved. And of course she became an old woman, a grandmother. If not doting, she was affectionate, full of pride and love for her twenty-five grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Still, my mother did not go gentle into that good night. I honestly don’t think she ever thought of herself as elderly, and though her stubborn resistance to things like wheelchairs and retirement homes brought her unnecessary heartache and her family endless frustration, maybe her stolid resistance to accepting the concessions of age was what kept her young-ish for so long.

A wearer of Easter hats, and yes, addicted to black coffee. A better piano player than she gave herself credit for, she was an admirable consumer of wine if not a connoisseur and a great fan of gifts, both received and given (accompanied by makeshift cards, always signed with love). Shopping! Boy did she love a good bargain, but the coup de gras of my daughter’s emoji-esque tribute? It has to be the stack of pancakes. A half-hearted cook otherwise, my mother made a damn good pancake, so light and fluffy we generally ate a few more than was advisable. Well into her nineties, she continued to host her in-town family for Saturday morning breakfast. Even on days she burned the bacon and stirred cornmeal into the batter when she meant to use flour, we wolfed it all down.

A couple of emojis I might add to my daughter’s thread … the jet plane, and the stack of books. A wannabe travel agent and a devotee of museums, ancient cathedrals, lush English gardens and French chateaux alike, my mother taught me that travel is the best learning tool we have, with reading a close second. She devoured books, and collected everything from Henry Kissinger’s memoirs to Virginia Woolf’s novels. For that legacy, with apologies to Marie Kondo, I am most grateful.

My Stats page tells me this is my thirtieth post in the Attic, thirty in about four years, though apparently I’ve shared nothing since last March. Maybe that’s a sign. Maybe it’s time to wrap it up. Lord knows (and as this post surely proves) I have repeated myself, circled around the same themes often enough. I won’t archive the site just yet, but I’m at work on a few other projects now. With luck, I’ll be able to share these one way or another before too long.

Those handy Stats also tell me upwards to six thousand folks have been kind enough to visit the Attic over its lifetime. They–you–have given my posts over ten thousand views. Thank you. Thank you for stopping by. Thank you for sharing the strangeness and laughter and joy and sorrow that come in the wake of losing a parent, no matter how old or young.

Happy 100th, Mom, our one and only.

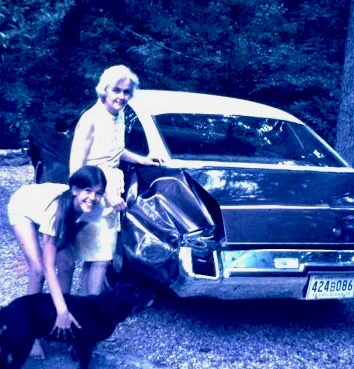

Not Your Mother’s Oldsmobile

Exhibit A: Me—twelve, Mom—fifty-four, family pooch—we’ll call it six. Her name, the dog, was Butchie, largely because the Mattingly dogs who preceded her, all male, were called Butch—Butch the first, Butch the second … George Foreman style, and if the tradition can be feminized, why not? The car (or perhaps victim?)—a convertible Cutlass, circa 1970. It belonged to my brother George (imagine that, Mr. Foreman), mid-twenties at the time and two years married to his lovely wife, Connie. Wait, it’s possible Connie brought the Cutlass in question to the marriage, a sort of dowry-like perk. Memory fails, but let’s go with that. It makes a better story, and for sure, I’ll never forget the happy couple’s gnashing of teeth after the incident that left their racy little Olds bashed at the hip …

Late spring or early summer, from the looks of my outfit, sunset of my seventh grade year, and apparently I’d set my sights on the Twiggy award (all arms, legs, and stringy hair). Late afternoon, as I recall, and I’m hanging out in our family den, a bag of potato chips and onion dip close at hand, maybe huddled over a pre-Algebra problem, maybe watching a “Brady Bunch” re-run, most likely fresh off the (rotary) phone from lamenting to a similarly pre-pubescent friend that my crush-of-the-month only had eyes for Laura or Cynthia or one of three other classmates more Bridgette Bardot-like, even at twelve, than Twiggy.

Suddenly, a high-pitched scream outside, at first faint then gaining volume like an oncoming train. I drop pencil and Lays and bolt out the back door, Butchie at my heels, to driveway’s edge. Our driveway (see Exhibit B below), ran about forty yards straight down at a precipitous angle from the street to our house in a hole, as I used to call it, a hole created in some long ago millennium by the babbling creek that flowed five to ten yards, give or take, to the right of said driveway. Just below driveway’s crest, a pile of mail in her arms and pocketbook swinging at her elbow, my mother chases as if to rein in with magical maternal powers her lemon yellow Electra, a popular boat-like Buick of the day. The Buick rolls merrily along, self-driven, ten feet ahead of her. I grab Butchie’s collar and freeze. The car seems more runaway cartoon buggy than dangerous projectile, and I sense in my mother’s screams more panicked embarrassment than fear. Sure enough, the hulking Buick all but eases over the wide drain at driveway’s base, where rainwater sluices away on a stormy day. Rather than careen toward the pup and me, she veers right, groaning, and comes to a cacophonous yet somehow graceful stop, her fall, so to speak, broken by the unlucky Cutlass situated in the handy parking slot my father cleared years before above the picturesque creek.

“Two cars! Two cars!” my mother hollers, spectator pumps slapping gravel and knees knocking beneath the hem of her skirt. Two car crash, she means, and the fact that she, whose exercise regimen features climbing steps and roaming the mall, has survived this descent without serious injury is perhaps most astounding of all. Her arms are empty now, spilled purse and mail littered across the drive, and she flails those arms overhead like a mad wing walker flashing his orange baton on a tarmac. I think I smile a little even then, because honestly, though this will be an expensive mistake, one that might have been tragic, it really is funny.

Moments before, the Electra’s trunk stuffed with grocery bags, Mom pulled over the raised lip that joined driveway to street and stopped, as she’d done countless times before, to fetch the mail. She mashed the emergency brake with her quad A, size 6, foot, opened the door, stepped out to the mailbox, and, ooh la la, there she went, Old Electra, smelling the barn and waiting for neither man nor dreamy woman. The gear shift, my mother surely thought. Did I put it in Park? She did not, and thus did the yellow workhorse begin her joyride home, happily slowed by that emergency brake. How was she to know my brother’s muscle car had claimed her favorite stall?

I wish whoever snapped this Kodak moment had included old Electra, whose escapade left her with quite a shiner (think of the Instagram likes Mom might have earned!), but otherwise, I love the old crash photo, grainy and blued as it is. I love the dense foliage in the background that was the leafy oak that used to shade my friends and me in the creek below as we hopped from rock to boulder, building dams and creating imaginary villages. I love the tall tree trunk to the right, one of so, so many towering pines in our Georgia yard. I love having a pic of Butchie, RIP ole girl, with her graying beard, and mostly, I love the amused look on my mother’s face, the hint of guilty delight that says she owns this crazy humiliating moment, much the way she owned others during her long wacky years of rearing six children.

It’s funny, I don’t remember much anger associated with the Cutlass caper—check that, George was pretty stoked, but who could blame him? I associate with it instead one of my father’s exasperated shrugs and the eye roll that often followed. Needless to say, our family weathered troubles much more serious over the years than a two-car crash (though how it must have stumped our insurance agent–who/what was at fault?). We weathered times that in the moment weren’t funny at all, but somehow, most of our dysfunctional moments did, in the retelling at least, dissolve into laughter.

It was all about sense of humor, and the fact that my mother and father managed to keep theirs, through better and much worse and even as they aged and life grew close and dark. That legacy is something I thank them for, every day.

To Know A Mother

Now that our nest has emptied, I have more time to think, especially during the unfamiliar quiet of morning. Gone are the frantic searches for blazers and ties on dress-up days, gone the burned toaster waffles and spilt milk, gone the forgotten permission slips. So I sit with my coffee and watch the sky brighten outside the window. I check the weather in all the places where my scattered children live. I read the news (too much news, and immediately regret it). I scan social media, pour another cup, play a few words on WWF, maybe do the Times Mini Crossword. I mean to write more, every day (you’ve got all this time now, finish that damn novel!), but thus far, the muse remains fickle and slow.

Today I woke determined. My nerves sparking with caffeine, I trained my index finger over to the Poetry app I installed, oh three years ago, thinking to read a poem a day for inspiration. (Total number read to date = five) Clinging to the idea that it’s never too late, I chose a theme, “Passion and Nature,” and waited to see what the Poetry algorithm would find. Never mind that by “passion” I meant fevered devotion to a craft, the app figured romance (…er eroticism). Still, a piece called “The Garden by Moonlight” caught my eye. Ignoring the sexual undertones, I lapped up Amy Lowell’s lyric imagery and the cadence of her simple sentences: A black cat among roses … Phlox, lilac-misted under a first-quarter moon … The sweet smells of heliotrope and night-scented stock … Moon-spikes shafting through the snow ball bush …

I thought of my mother, and the cut flower bouquets she had such a knack for, the postcards she used to send from gardens around the world, the places she took me as a child: Kew, the conservatory at Golden Gate Park, Monet’s gardens at Giverny (I know, lucky me). I read on to Lowell’s final quatrain in which–what a wonder!–the narrator speaks of her own mother: Ah, Beloved, do you see those orange lilies?/They knew my mother/But who belonging to me will they know/When I am gone?

A ping and there’s an email from my sister, reaching out to my brothers and me on the anniversary of Mom’s death. Yep, it’s October 19. My mother has been gone three years exactly. Next Wednesday marks the day my father, whose birthday we remembered October 9th, died fourteen years ago. As I’ve written here before, October has become a month of emotional contradiction for our family, and 2017 has not disappointed. While I was dashing between a big birthday bash for a dear friend and my niece’s wedding in Philadelphia (which morphed happily into something of a family reunion), our second son’s longtime girlfriend, a young woman our family cherishes as one of our own, lost her mother. She was hardly into her fifties, as brave in standing up to the terminal brain cancer she lived with for eight years as she was determined to be present for her children as long as she could.

So mother-loss has been on my mind for lots of reasons. Of course, losing a mother at fifty-four as I did hardly seems worth mentioning compared with losing a mother at twenty-five. And yet what the heart registers, what we share no matter when such a loss comes, is a sort of sorrowful disorientation. How do we step forward without the person who so often, for better or worse, has blazed the path we follow?

The thing is, the beating hearts our mothers gave us are built for more than sorrow. Much more. Along with conflicting feelings, they hoard images, words, memory after memory of the people who move in and out of our lives. Maybe what the poet Lowell implies with her black cat and her moonlit poppies then is something simple, something I know but have to keep re-learning: As long as we take time to share these heart-borne images and memories, to repeat them and pass them along, whether through the written word or music or painting or just plain storytelling over a good meal, we give new life to those we’ve lost.

A few years ago, my daughter and I visited Giverny together. Not unlike Lowell’s lilies, the cascading wisteria, the rows and rows of forsythia and zinnias bursting gold and red against the Monet-blue sky, they knew my mother, who made sure they know me. And now, they know my daughter, too.