Life on the farm in Depression-era Alabama

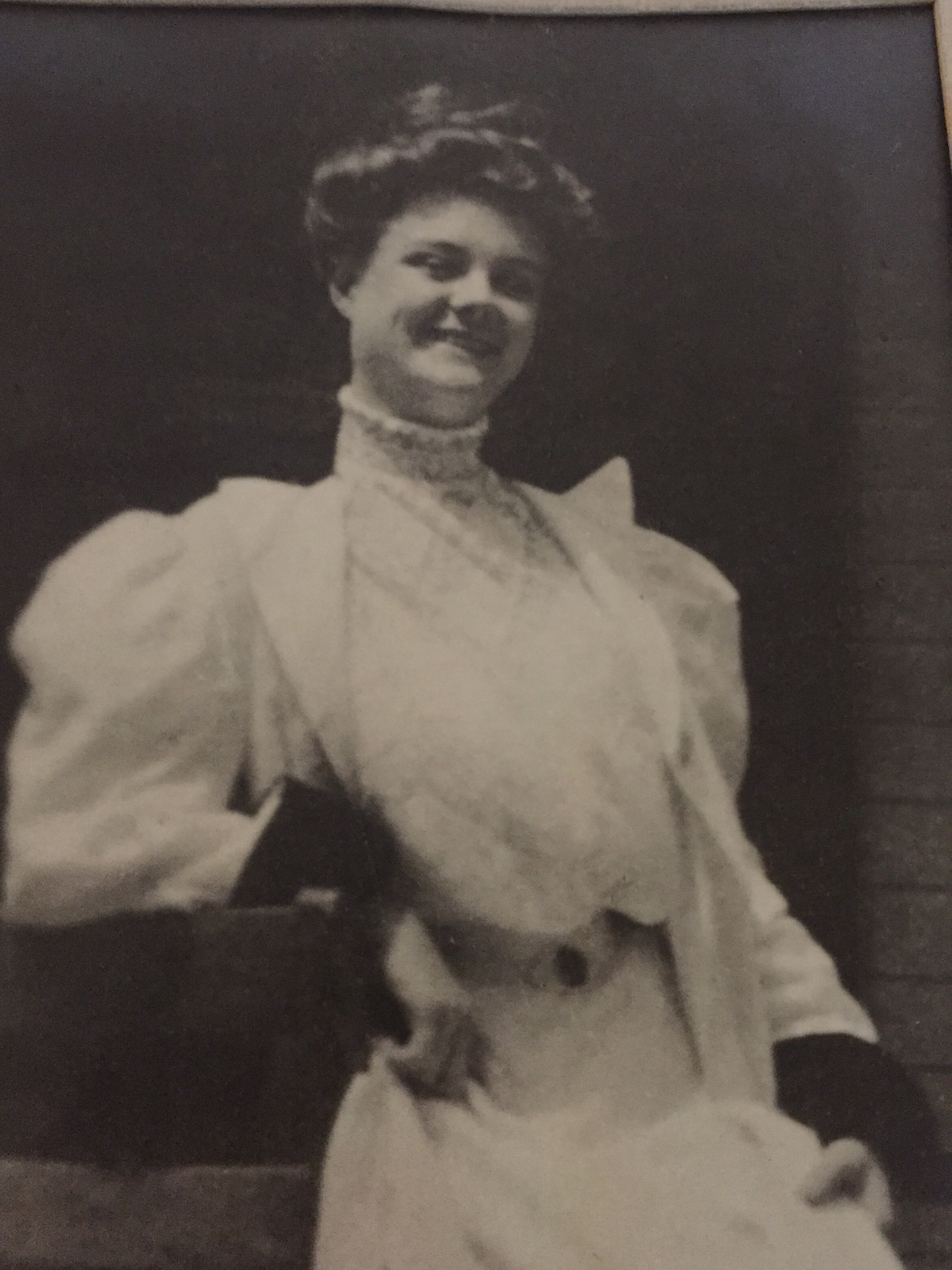

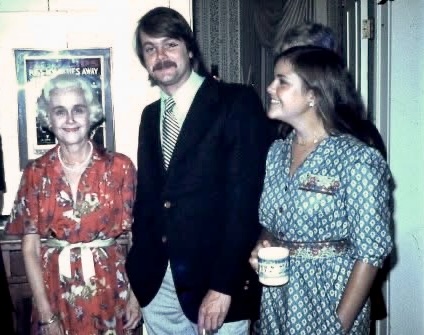

In memory, my first few visits with Mary Darian are fresh and bathed in light. It was spring, 2017. From where we gathered in her daughter’s living room, we could see Lou’s back yard, the lawn greening and her plantings touched with early spring color. Yes, Mary was still grieving the loss of her oldest son and recovering from a fall. Her speech was sometimes halting, especially when she grew tired, in the wake of her last stroke, but for the most part, she was upbeat, both determined to do her therapy exercises to regain her strength and eager to share the story of her childhood. Her Alabama family was cash-poor when she was growing up—she made no bones about that—but when she described her young parents and her grandmother and great-grandmother, her expression warmed. Sometimes, her voice was tinged with longing, a longing for the simple life her family built out of next to nothing.

Which is not to say Mary romanticized that rural mid-20th century life. She’d lived in Atlanta since she was fourteen. She’d experienced unrest, boycotts, and violence just to earn for herself and her loved ones basic rights she lacked as a child—the right to sit where she pleased in a theatre, to use a public restroom, to vote. Like other Black tenant farming families in the Deep South, during her childhood the Walkers and Cochrans were trapped in a dead-end economic system. The threats and humiliations of Jim Crow hung over them like a shroud. “You couldn’t make a living in Hurtsboro,” she liked to say. “Hurts to stay there and hurts to leave.”

But Mary was the walking example of the old adage that the key to happiness is to want what you have, not in the sense of surrender but in making the best of what’s given you in any particular moment. I’ve been pretty bad at this most of my life, always striving for something or other just out of reach. Maybe that’s why being with Mary in Lou’s sunny home, just being with her and listening to her stories, no matter how surprising some of them were, was such a comfort.

When Mary Lue Cochran was born on November 11, 1935, her father, Jimmie Lee, was twenty. Her mother, Lue Milla James Cochran, was seventeen. Mary’s brother Leroy came along a year later. I asked Mary one afternoon whether her mother had to join her father in the cotton fields to meet the quota that paid their rent.

“My daddy …” she said, shaking her head. “Also worked at the Perlmans’ store. That extra money he made kept my mama out of the fields after I was born. She stayed in the house working and taking care of Leroy and me.”

The Perlmans, an immigrant Jewish family, owned a dry goods store in Hurtsboro. Strange. I knew that as Atlanta’s population boomed in the late 1800s, the city began to attract immigrants from all over Europe, but Hurtsboro? A town that grew up around a sawmill in the 1850s situated in remote eastern Alabama, in 1900 it had just over 400 residents, most of them farm laborers or mill workers. I decided to do a little research. Turns out that of the influx of Jewish immigrants fleeing the pogroms and economic hardship of Eastern Europe around the turn of the 20th century, many wound up in small Southern towns working as merchants or peddlers. So the Perlmans’ store wasn’t strange at all. I checked out the store owner Sol Perlman on Ancestry.com and managed to locate his son. Sam Perlman, who spoke affectionately of growing up in Hurtsboro, shared that his grandfather Henry had immigrated to Montgomery from Lithuania in 1891. A few years later he took out a loan to open a store sixty miles southeast in—you got it—Hurtsboro. Henry Perlman was a smart cookie. Two railways served by a shared depot had just been extended through the middle of town, and though one Ben Goldstein, originally of Poland, already ran a general store there, they both wagered there’d be business enough for another. They were right. A golden age followed. By 1914, a year before Mary’s father was born, the sawmill town boasted an inn, a cafe, those two general stores and a couple of banks. By the time Mary was born, the population had more than doubled and two hardware stores, a library and a movie theatre had sprouted up. Henry Perlman, and later his son Sol, much like Ben Goldstein and his son Abe, did good business, not only with rail passengers passing through but with tenant farmers, providing them with fuel, feed, kitchen staples and other goods. Southern landowners generally preferred it this way. By sending their tenants into town for supplies, they could leave unpleasant matters such as late payments or poor credit to the shopkeepers.

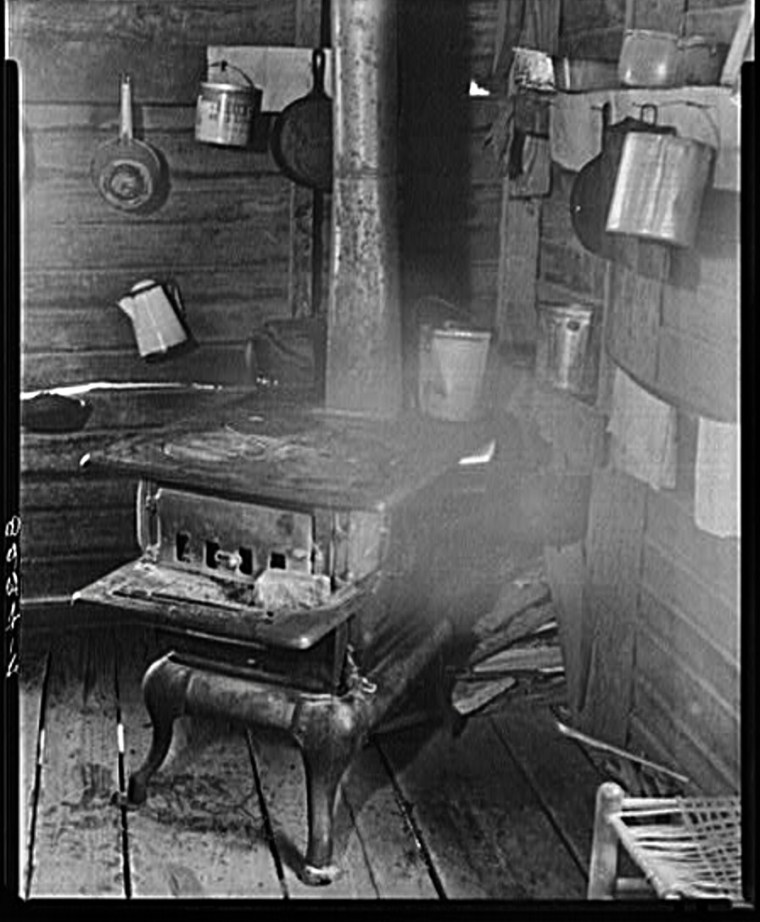

Another smart cookie, Jimmie Lee Cochran was also a hard worker. Not only did he do maintenance work for Sol Perlman, he became a chauffeur for both Sol and Abe Goldstein, whose store was a short walk up Main Street. When his work was done in town, Mary’s father walked back to his family’s rental property a few miles outside of town, a two-room clapboard house with straw mattresses, “a big fireplace for heat,” windows that had shutters “you could close at night or when it rained,” but no glass panes. And an outhouse out back.

“We had a well for water,” Mary said. “That was the best water, just as cool as it could be. And Grandma Ca-line had a little garden of her own …” she added, full of pride. “She grew lettuce, carrots, corn, cucumbers, plums … Mm—mmm.” She smiled and smacked her lips. “Ma Sweet had a little store by the side of the house and folks would come by and pay her a little to go pick whatever was in season straight from the garden. They knew it was fresh that way. Ca-line raised chickens, too, and sold eggs. That’s how we had income.”

“Ma Sweet” was Mary’s father’s mother, the younger Ellen in Mary’s family tree who had attended a few years of school and was the entrepreneur of the household. She earned her nickname not only by baking sugary concoctions like tea cakes for the white family she worked for but also stocking in her store penny candy, RC cola and Nehi (“from the icebox”), goodies she bought from a traveling peddler.

“Ma Sweet and Ca-line used lard. Everything tastes better with lard,” Mary laughed. “Ooooh, those biscuits! I get hungry just thinking about them. And you know, all we had was a pot-bellied woodstove with two eyes—how’d they cook all that and make our meals, too? And honey, Ma Sweet bought lemons from that peddler. She had us roll and roll them until they got soft. Then we’d squeeze out the juice and she’d sweeten it up with sugar or honey—I never knew which I liked best. She sold that lemonade and mint tea in Mason jars.” Mary paused, her gaze turning inward as she drifted back in time. “Mint tea was a good thing.”

“Oh! And blackberries!” She snapped back to attention, her soft brown eyes bright. “I almost forgot about blackberries. We picked them to eat and Ma Sweet sold them. That’s the other sticky thing I didn’t like.”

The other sticky thing … And the first? Maybe I was naive, but that first sticky thing had surprised me.

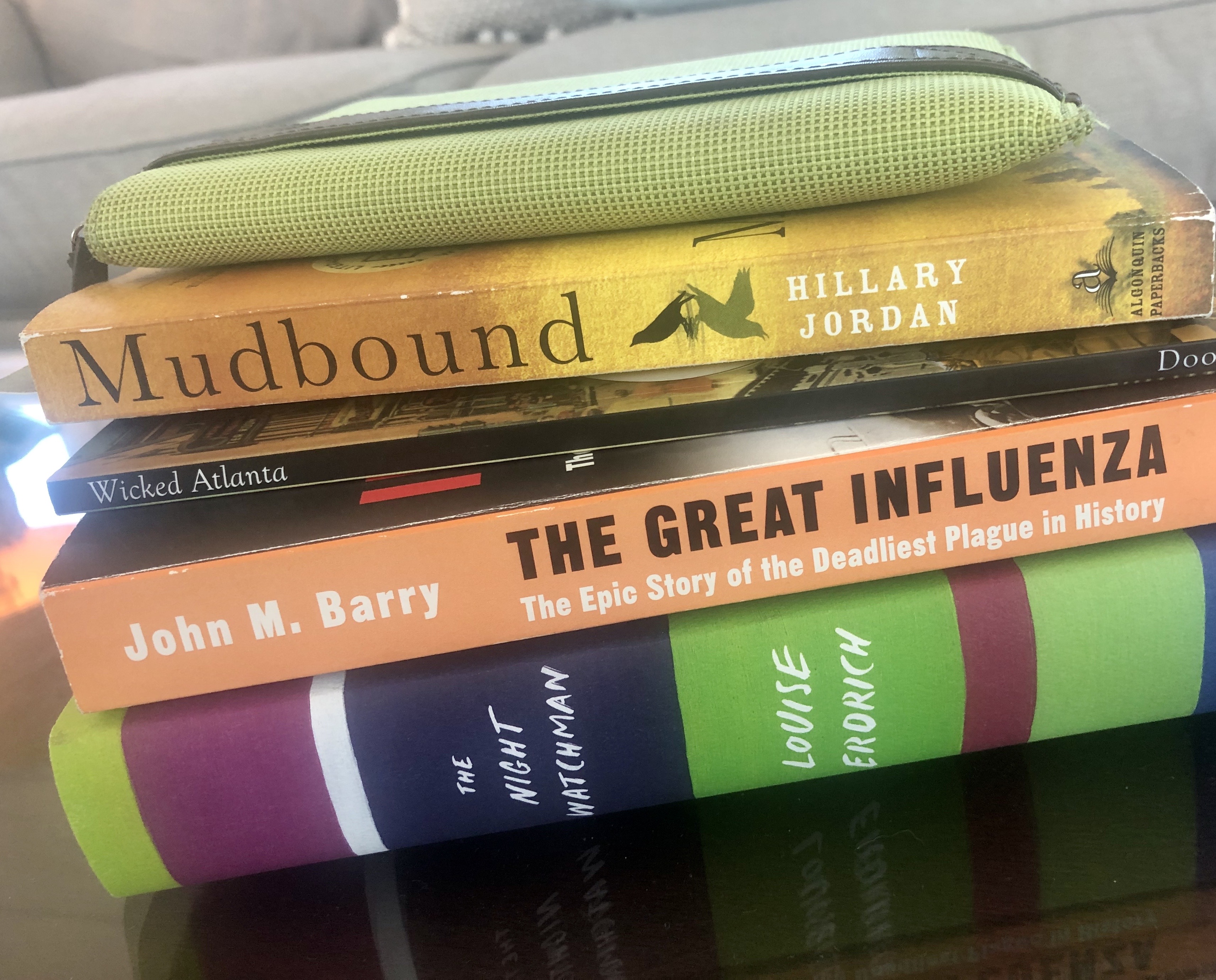

“You picked cotton?” I’d asked, struggling to mask the shock in my voice. The Mary I’d known was a spunky young city woman, clever and streetwise with a sophisticated wit. A city girl myself, I’d never known anyone who worked a farm—well, that’s not altogether true. A cousin of mine owns a ranch in Colorado, but managing horses and livestock, brutal as I’m sure it can be, seems different from manually tending a crop. When I pictured the child Mary bent over a row of cotton beneath the punishing summer sun, I could conjure only something distant and unreal, a downtrodden character in a movie or novel. But Mary’s experience was as real as it gets.

“Yes, I picked cotton as soon as I was able. We kids started, oh I guess we were seven or eight years old. It was the dog days, all summer right up through Labor Day. The boys had to pick after school, but we girls didn’t.”

I was rapt.

“We had a sack we carried over our shoulder,” she went on. “You picked off the hard brown bolls, they were like a little hard flower with a thick husk and the end of it was sharp and sticky. You had to take off the boll and pull out the little seeds before you dropped the cotton in your sack. Once your sack was full, you brought it so they could weigh and bale it up.”

How much cotton was expected from each of these second and third graders?

“The owner of our patch liked us to pick a hundred pounds a day.”

Quite the taskmaster, King Cotton.

Mary’s story will continue next time in “Sharecropper’s Daughter, Part II.” Until then, I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comment box below, and thanks always for reading “Afternoons with Mary.”

Honestly, I’m not sure this is true, that my mother taught me to read. I recall

Honestly, I’m not sure this is true, that my mother taught me to read. I recall