During a late sweep through the dark corners of my mother’s attic, I stumbled upon a moldering shrine to one of my paternal great-aunts. Louise Bickers, a.k.a “Weezer,” was a feisty single woman whom I loved like a grandmother. With affectionate if drowsy interest, I dragged over a rickety wooden stool and dusted off her leftovers—stacks of limp letters, photos with curled edges, family trees scribbled on yellowed paper, and a decomposing shoebox of daguerreotypes.

Stumped? So was I. An early form of photograph produced by “fuming” mercury vapor onto silver-plated copper, the daguerreotype was introduced in 1839 and became obsolete by the 1860s. The 1860s! And there I sat, a hundred and fifty-plus years later, with several in passable shape. I ran my finger along the hammered tin frames, eyed the elaborate clothing, the formal, sometimes severe gazes. Where did these people—certainly family—live? What did they do? My curiosity piqued, I tucked the least fusty samples into a fresh plastic bin beside far too many of Weezer’s letters and photos and family trees, and moved on.

During the pandemic’s endless, vacant shut-in hours, I fetched up those family trees, rebooted my Ancestry.com membership, and typed in name after name. It was fun, by 2020 standards, learning how to create profiles for my long-lost blood kin and search for relevant documents and photos. When a grainy image of one of my great-great grandfathers popped up, I knew immediately it was—you got it—a daguerreotype. I fished out Weezer’s frames to compare and contrast. None of the faces matched exactly, but they favored, as my mother would say.

At once piercing and playful, my second great grandfather’s gaze seems especially, hauntingly, familiar. Born in 1825, Thomas Blake Bourne descended from a long line of tobacco planters in Calvert County, Maryland, a leg of land that kicks out into the Chesapeake Bay. The Census of 1850 valued his property at $2,500, equivalent to about $150,000 today, making his a healthy if small farm for its time. I can’t pinpoint the farm’s exact location, but odds are it was on or near Eltonhead, a tobacco manor along the instep of the county’s watery foot, tracts of which had belonged to Bournes since the late 17th century.

A city girl, I smiled to picture my great-great grandparents, Thomas and Margaret Louisa, living their quaint, rural 19th century lives. Soon a marriage record surfaced from May of 1848, a photo of Thomas’s gravestone, the inscription honoring him as “… a devoted husband and father, true to his friends and his country,” and a certificate proving that his maternal grandfather, Colonel Joseph Blake, fought in the American Revolution. Cool. I’m a DAR. I felt all rosy with pride. Then something else, less than quaint, caught my eye—a Slave Schedule, an appendix to the 1850 Census in which enslavers identified their “human property,” not by name but according to age, sex and color. I blanched, my ancestral pride dissolving as I counted the tick marks beside Thomas’s name: an even ten, six black males and four black females between the ages of six and forty-five.

I attached the Slave Schedule to Thomas’s profile and clicked back to his daguerreotype. That playful grin … might it be more a cunning smirk? My forehead heavy in my palm, I called my daughter in New York.

“We are from the South, Mom,” she said, unsurprised.

“But your grandfather came from humble roots,” I argued. “And Maryland’s hardly the South …”

“I know, Mom,” she said gently, knowingly. “But even small farmers enslaved workers back then.”

Which I knew, but this was our family, a whole different ballgame. I hung up and returned, dull eyed, to my laptop screen. Lined up in the right margin, I noticed tiny circular photos I’d missed before, profiles of other genealogists who’d saved Thomas Bourne’s image. I hovered over one, then another and another, and a pattern emerged—many belonged to people of color. What’s more, the family tree associated with each profile included a common ancestor, a man named Louis H. Bourne.

With clammy fingers, I typed Louis’s information into the Ancestry search engine. My first hit was the Census of 1860, which lists Louis H. Bourne, born 1830, as a “mulatto” head of household and farm laborer in Calvert County. More hits revealed that by 1880, Louis and his wife, Margaret, had purchased over thirty acres of land and settled down to farm tobacco in Island Creek, a breezy community along the Patuxent River that lies about fifteen miles from where Thomas Blake Bourne lived with his family.

Or used to live. In 1855, amid rumblings of the war to come, Thomas had moved his household—including three children and at least nine enslaved persons—across four rivers and the Mason-Dixon line to a manor house near the James River in Virginia, a state he surely wagered would prove friendlier to his future as a planter. Eight years and three children later, Thomas enlisted to fight for the confederate states. He was thirty-eight. Around the same time, Louis H. Bourne, thirty-two, signed on with the Union Army. And so it was that second cousins, as I believe they were, took up arms against each other in a war rooted in misconceptions and greed. Were Thomas and Louis aware of this? I suspect so. It was a much smaller world then and Thomas still had family aplenty in Calvert County. Both men survived, though my great-great grandfather would die suddenly ten years later, the youngest of his nine children only eleven years old.

As intrigued as I was conflicted, I reached out to a few folks whose trees included Louis Bourne. Responses were scarce, but eventually I heard from Florencetine “Tina” Bourne Jasmin of Baltimore County. I hesitated–what right did I have to barge into her life?–then dove in and wrote to her that we could be related, somehow, through Louis Bourne.

“Oh my gosh,” Tina responded. “I’ve been hoping to find someone who might know something about my great grandfather!!!” Smiling again, I shared a little about my family. Tina sent photos of her son and daughter and grandchildren. She told me Louis Bourne had remained—thrived—in Island Creek until his death at seventy, as did many of his children, and some of theirs, and theirs and theirs right up to the present. Louis and Margaret had eleven children, among them trailblazers who stared down the fetters and hostilities of the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras. One of their sons, Ulysses Grant Bourne, was among the first black physicians to practice in Frederick, Maryland. A grandson, James Franklyn Bourne, Jr, was the first black judge to serve on the district court for Prince George’s County. Quite a legacy, an improbable triumph in fact, and this was only the beginning.

At some point, I told Tina I regretted the unspeakable abuses my ancestors had visited on hers. “This history is beyond our control,” she mused. “I want to believe our ancestors are pleased with us for trying to reconcile our past.” Awed by her tolerance and wisdom, I thanked her and we dug in, working to make sense of our family ties. Tina quickly shared her best clue–a digital copy of Louis’s death certificate which names his mother as “Gracey Mason,” and his father as “James Bourne.” James Bourne? Thomas’s father, my third great grandfather, was named James. But then so was his oldest son, and his first cousin, James Jacob Bourne. Which James fathered Louis? And did he enslave Gracey Mason and the son they shared? Hard to know. A pair of 19th century Calvert County courthouse fires destroyed wills and bills of sale that might have given us proof.

We called in help. Tiffinney Green of Baltimore, Delma Bourne-Parran and Patrice Evans of Prince Frederick, and another cousin in California, all descendants of Louis Bourne, joined our search. The emails flew. We shared trees, unpacked oral history. Hoping to discover shared DNA, we spit in vials, waited, and waited some more.

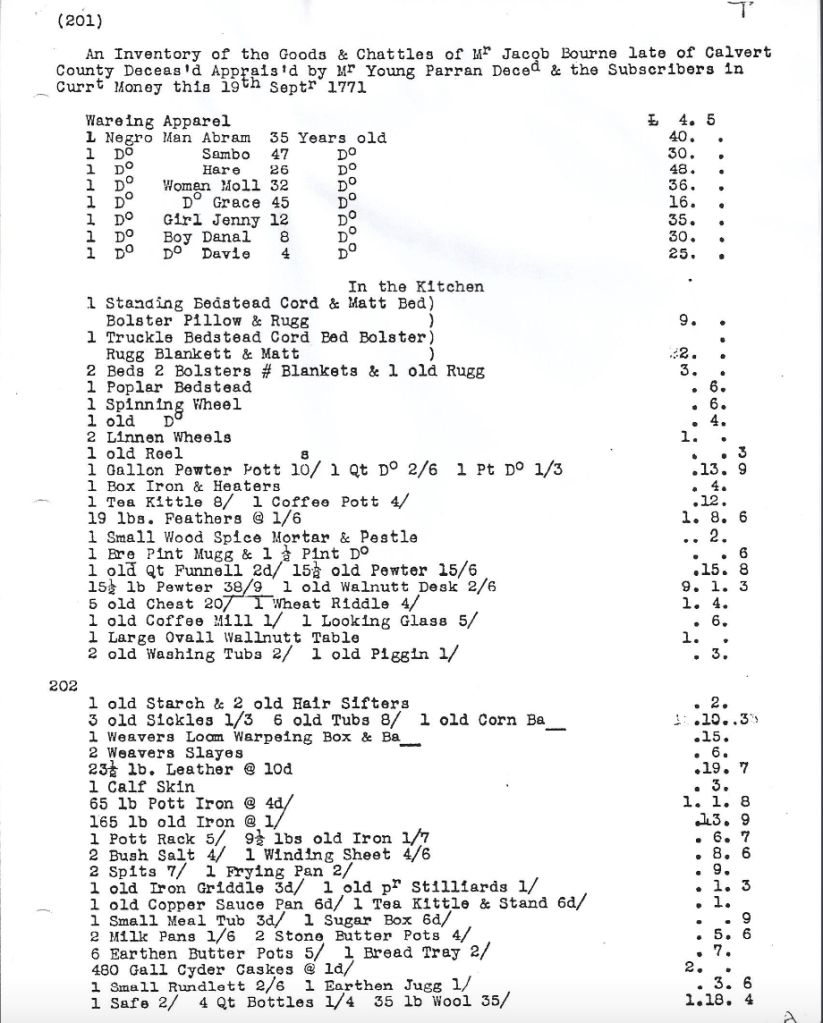

The results: Delma, Patrice and Tiffinney each match with at least one of my distant white Bourne cousins. And the kicker–Patrice’s sister and I share DNA. Heartened by this proof of our kinship, we analyzed and drew charts and at last wagered that James Jacob Bourne (1791-1850), an enslaver of twenty-two, most likely fathered Louis H. Bourne. This means our common direct ancestor is my fifth great-grandfather, Jacob Bourne (1721-1771), whose will survives with a full inventory attached. In the same figurative breath as a tea kettle, three old sickles, and the spinning wheel in the corner, Jacob names Grace, age forty-five, as one of several enslaved people to be “gifted” to his sons. Might this Grace have had a granddaughter who was passed down the line to James Jacob? It was common after all for baby girls to be named for a grandmother.

Due to those courthouse fires, for months we had little else to go on. Then Tiffinney found a Grace Mason, born 1807, listed in a Calvert County registry of Free African-Americans in 1832. She lived with a Hannah Mason, age forty. A Louis Mason, age two (just Louis Bourne’s age), also appears in the registry and seems to have been part of Grace’s household. Grace and Louis Mason then disappear. Free people of color were often servants in households that enslaved others, and our hunch is that Grace Mason worked for James Jacob Bourne. Maybe at some point, say when Louis was a child, James took in Grace and their son, maybe even enslaved them in some sort of twisted effort to control them. Did Louis Mason then become known as Louis Bourne? Did James Jacob later free his son who should have been free all along?

We’ll likely never know the full truth. The fact that Louis shows up in the 1860 Census means he was a free man well before Maryland officially emancipated its enslaved. Hannah Mason, the woman listed alongside Grace in the 1832 Registry, provides another clue. Louis’s 1860 household included a Hannah Mason, age seventy-four. Though the years don’t quite match up, they’re close enough for that era to suggest that Hannah was Louis’s grandmother, and that her daughter–Louis’s mother, Grace–died young.

Unless James Bourne sold Grace off.

“I pray that was not the case,” Tiffinney wrote to me.

I pray so, too.

Much work remains. Most of my family lines run back to the colonial era, where other fraught relationships lie in wait. Tiffinney and I have DNA matches in common that suggest we may also be kin through my Mattingly side, and I’m in touch with another young woman directly descended from Colonel Joseph Blake. Looks like the Colonel’s son had his violent way with her third great grandmother.

In May, my sister, JoJo, and I visited Calvert County. We researched alongside Tina and Tiffinney, and after, the four of us gathered for dinner with Patrice, Delma, and Marietta Bourne Morris, who still lives in Island Creek. We bored each other with family stories. We laughed over wine and margaritas. Humbled, JoJo and I accepted the kindnesses these women offered. Strong one and all, they overlook with seeming ease the troubled origins of our relationship and accept us as family. I’m proud to call them cousins, hopeful that Louis and James Jacob, Thomas and Grace Mason and my great aunt Weezer are indeed pleased.

Moving forward, I’m not naïve enough to expect from others the open-hearted welcome I’ve received from the Bournes. It’s nothing I deserve. One thing seems certain—this is not a tale of two cousins. It’s a tale of hundreds, thousands—dark-eyed and green and blue; blonde, red-haired, brunette; Irish and Bantu and Latin, Nigerian and Welsh and Congolese. Our skin shines ebony and alabaster and every hue between, and our cells quiver with the tangled threads of those who came before us, our human race.

Postscript: If this sort of research project interests you, message me below or through Facebook. I’m happy to share tips and links to resources. There are many!

Your best yet!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks, Jill!

LikeLike

Dearest cousin,

Again, thank you so much for reaching out to me and sharing the experience of finding our Bourne family connection. I’m proud to call you family! ❤️

Sisi ni sawa!

Tina

Florencetine Bourne Jasmin

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, dear Tina! 💜💜💜

LikeLike

Oh Martha, Tina and our other wonderful cousins! I read this with both tears and smiles, remembering the dinner and laughs we all shared together in Maryland. It was such an honor and a pleasure to be with each other. Like Martha, I have very mixed emotions about our family history, but feel so positive about rediscovering what family truly means – loving, laughing and sharing. JoJo (Martha’s sister and cousin to all).

LikeLiked by 1 person

So well said, Jo! Thanks for sharing so openly about our experience 💜

LikeLike

Very interesting and well done Martha, and i dont think you owe anyone an applogy – you are a leader for civil rights, you are kind and treat everyone equal, your children share those values – you cant take responsibility for the actions of your family over 150 years ago – Its analagous to the stereotypes of the dutiful housewife and the husband that our grandparents observed – human progress has made those norms a thing of the past

LikeLike

Point taken, Bill. Perhaps apologies are not necessary but recognizing the ills of the past can help us build bridges and move ahead with hope. Thanks for reading!

LikeLike

Loved reading this, Martha. An inspiring story and beautiful extended family!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Laurie! I agree 🥰

LikeLike

Great work Marth! Intriguing and inspiring. Your passion and creativity shine.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks, dear Ceil 💕 Hope you’re well!

LikeLike

Martha I rarely look at FB but your story caught my eye. My mother was big into geneology as well and I too have some of those 1850 photographs and letters. Perhaps some day you can help me decide what to do with them!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Would be happy to! Thanks for reading Kathy 💜

LikeLike

So interesting and wonderful that you found each other. Love everything you share!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Katherine, for being such a loyal reader 🙂

LikeLike

Hi, I too am a direct descendant of a slave and Col. Blake. I would love to get in touch with you! This is so exciting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Traci, Very exciting indeed! I will reach out to you via email. Thanks so much for checking in!

LikeLike

A friend shared very interesting read last evening, as I sat with my husband John Joseph Bourne & his oldest brother Thomas Blake Bourne X!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh my! You must be family … Thanks for dropping in and reading. Is that TB Bourne the 10th?

LikeLike